February 2013

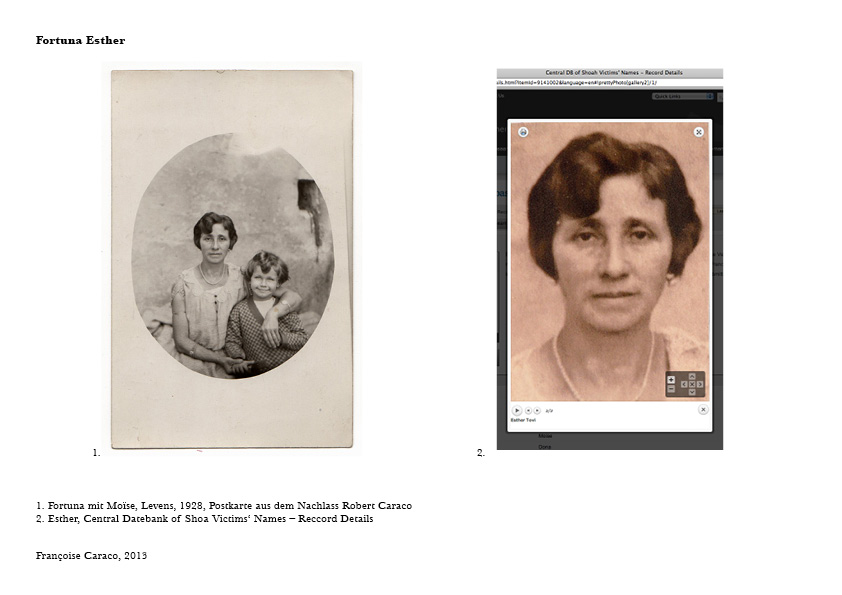

February 2013Fortuna Esther

Lecture performance by Françoise Caraco for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion (Foregoing, Fake, Fiction), teamwork with Nicole Biermaier, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Beiblatt zur Lectureperformance von Françoise Caraco, Fortuna Esther,

Fortuna Esther (2013)

Lecture performance by Françoise Caraco for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion (Foregoing, Fake, Fiction), Corner College, Zurich

In my lecture performance, using the example of a private family photo I recount how problematic I found it can be to retrospectively reconstruct the existence of a deceased person when their history is fragmentary.

I discovered two photos of a women who is related to me, each of them with different identifications, on the one hand as Fortuna and on the other as Esther. It becomes doubtful whether as evidence photographs have the power to foster personal identity.

There is no doubt that both Fortuna and Esther existed: both are mentioned in my grandfather’s ancestral tree, both are likewise listed in a database of the Shoah. But which one is sitting facing me on the photo holding the young Moïse in her arms remains obscure.

January 2013

January 2013Family Photos I,II,III (version1)

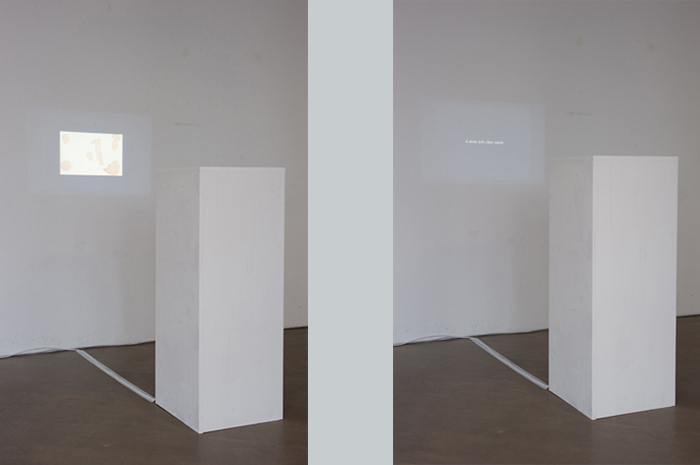

Exhibition view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion (Foregoing, Fake, Fiction), teamwork with Nicole Biermaier und Irene Grillo, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Exhibition view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion (Foregoing, Fake, Fiction), teamwork with Nicole Biermaier und Irene Grillo, Corner College, Zurich 2013

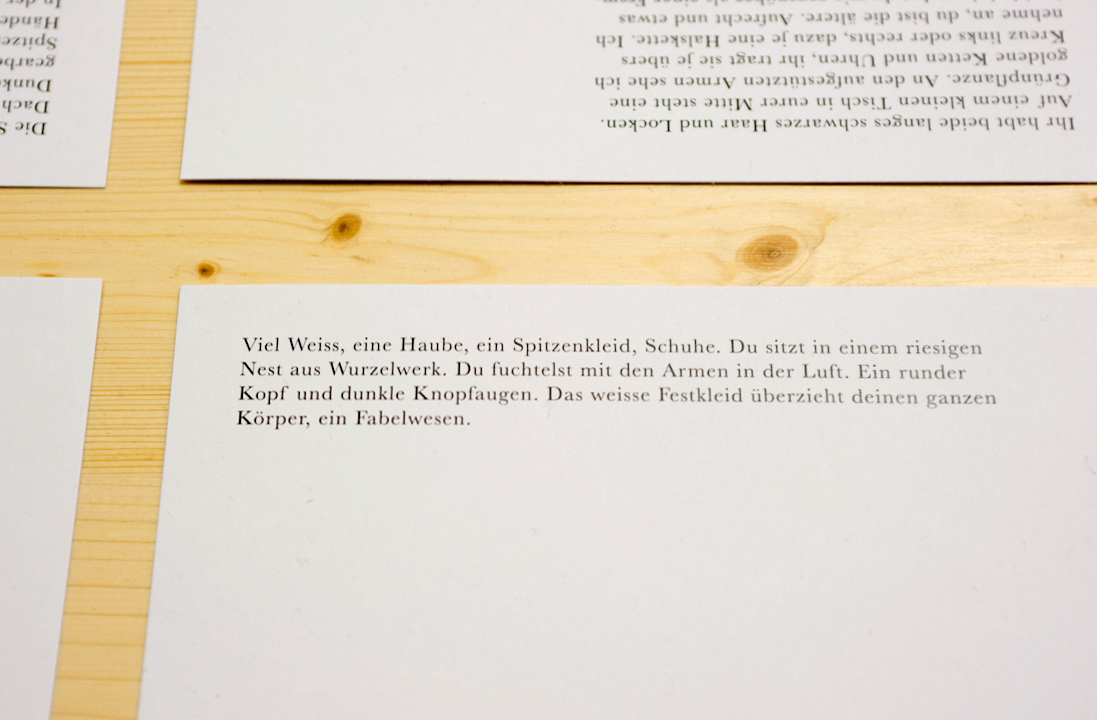

Detail view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Detail view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Detail view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Detail view, Familienfotos I,II, III, for the exhibition Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion, Corner College, Zurich 2013

Familienfotos I, II, III – Family Photos I, II, III (2013)

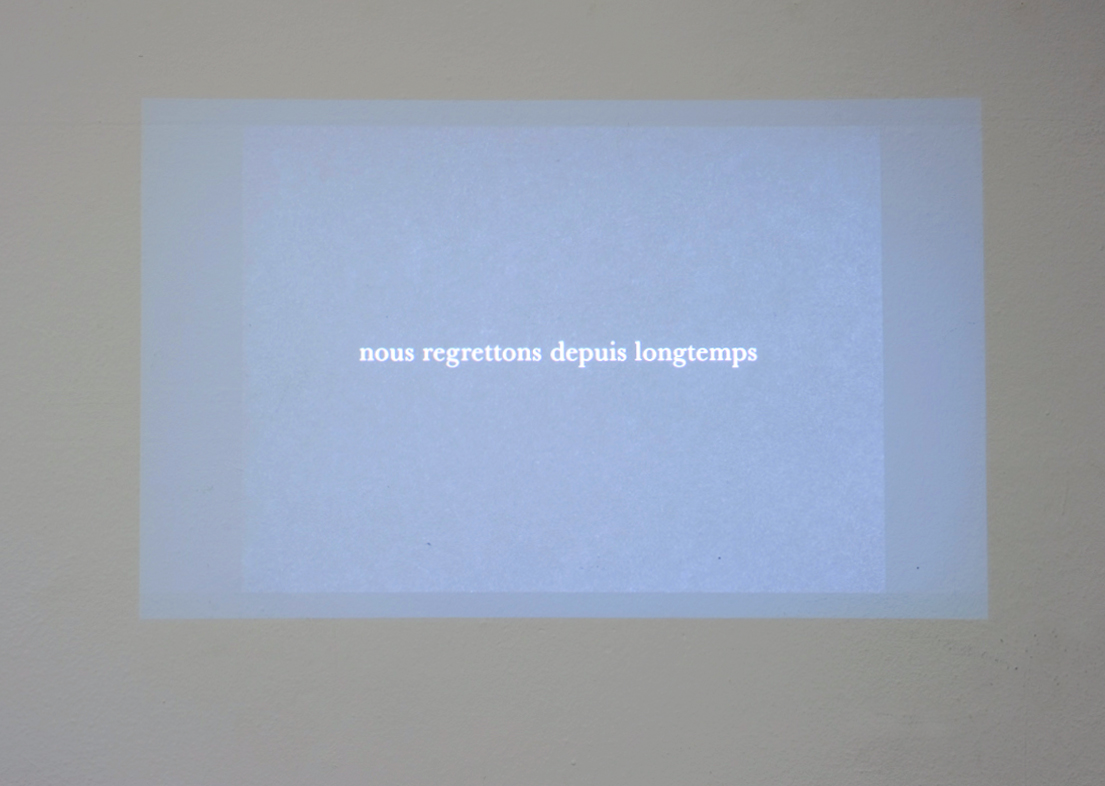

I: Video projection, HD 16:9, time 2' 33", in loop

II: 26, A5 filing cards, laser-print on paper

III: Audio work, time 5' 30", loop, speaker Esther Becker

Françoise Caraco tackles the story of her grandfather’s life. In the process, the absorbing of her own personal family history represents a gesture of connection: it serves her as an opportunity to reconstruct and reflect on the public and political circumstances of a bygone era. In the work Familenfotos, Françoise Caraco constructs an experimental layout of familial and social belonging and broaches the subject of the demarcations involved. To do so she uses portrait pictures and fragments of information from letters from 1904 to 1942 kept by her grandfather, the son of a Sephardic-Jewish immigrant from Istanbul.

Family Photos is a spatial installation in which Françoise Caraco stages a collection of photos and text fragments inherited from her grandfather. From her own contemporary perspective Caraco repeats her grandfather's attempts, based on family photos and written documents, to ascertain the presence of his relatives. The basis materials for Caraco are photographs, postcards and letters that relatives sent from their respective new ‘home countries’. In Caraco’s presentation these items become historic documents, revealing less about the concrete life situations of the family and instead posing more questions about public states-of-mind as seen from an intimate perspective.

The artist has taken the available and patchy archive material from the early twentieth century, carefully reviewed it, interpreted the content and formally transformed it. The customary black-and-white family portraits from the epoch have been translated into short texts in which she tries to descriptively reconstruct the interrelations between the depicted people themselves and with the simultaneously transported contexts. Caraco deploys an actress to read aloud the written details of the dates and locations derived from the respective pictures in the form of a mundane list. The empty reverse sides of the photos on which family members are shown are transformed by the artist into abstract pictures, projected in sequence with textual fragments from the written correspondence onto a wall. Using these three forms of translation Caraco reconstructs links and correlations that generate a new present-day image of the past. At the same time the blank reverses and the fragmented texts indicate losses and voids.

Familienfotos queries the medium of photography in the widest possible sense as a form of documentation. What can photography transport and how? What are its claims to truthfulness and its possibilities? Caraco understands a photograph as a document that is not always readily legible. As such, to begin with she found the photographs left by her grandfather indecipherable. She was unable to either recognise or sort the people depicted. Based on the identical source material, in an attempt to make it decipherable Caraco evolved three different forms of translation that endow the fleeting documents with a new coherence. Whether a private past can be reconstructed from these translations remains moot – the question being whether the product is not simply a construed reality, a fiction. It is precisely at this crux that we are re-confronted with a paradox expressed by Hito Steyerl: ‘Doubts as to their truth-value do not make documentary images weaker, rather stronger.’

Text: Irene Grillo, 2013