July 2017

July 2017Distance in your eyes

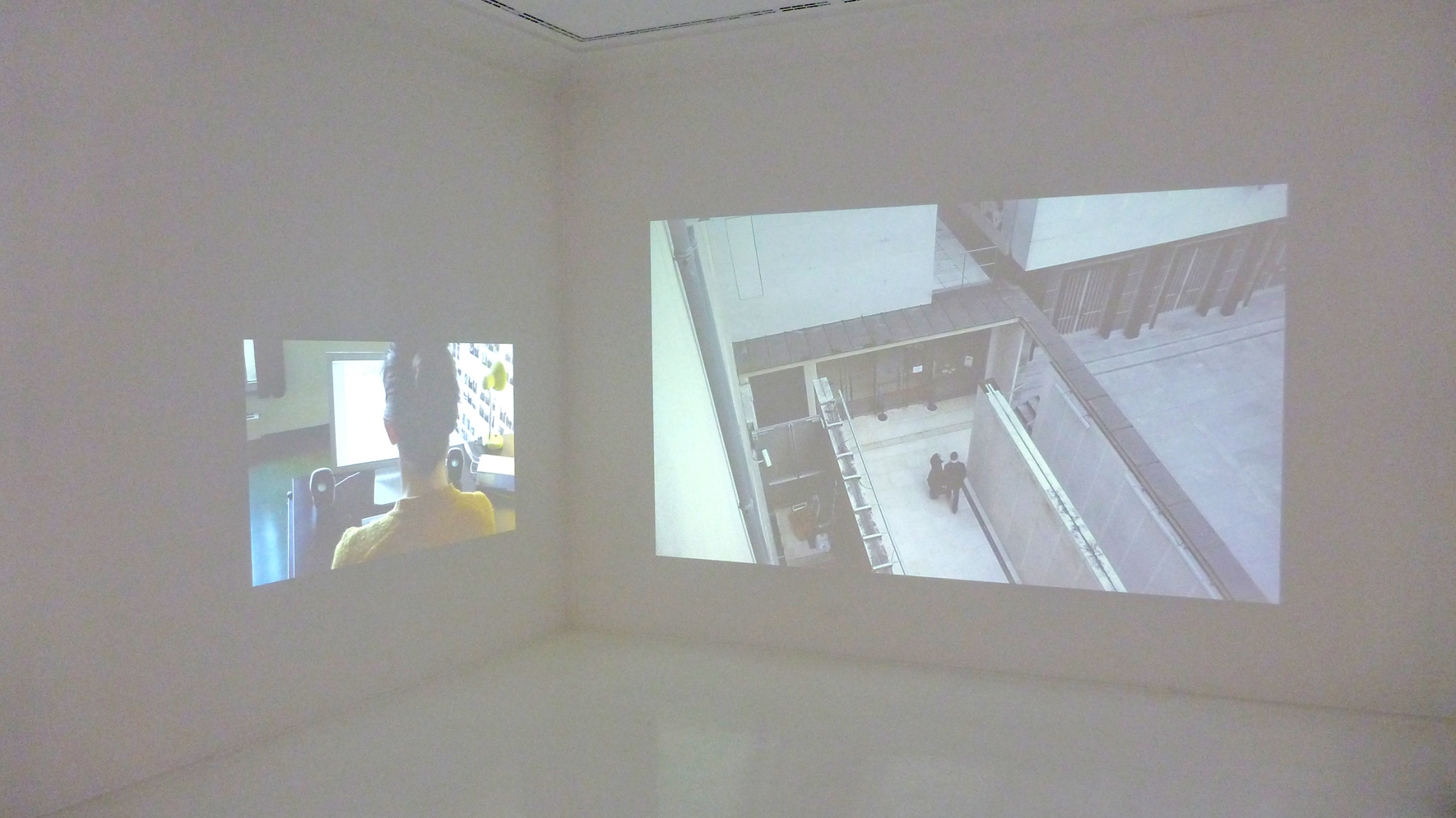

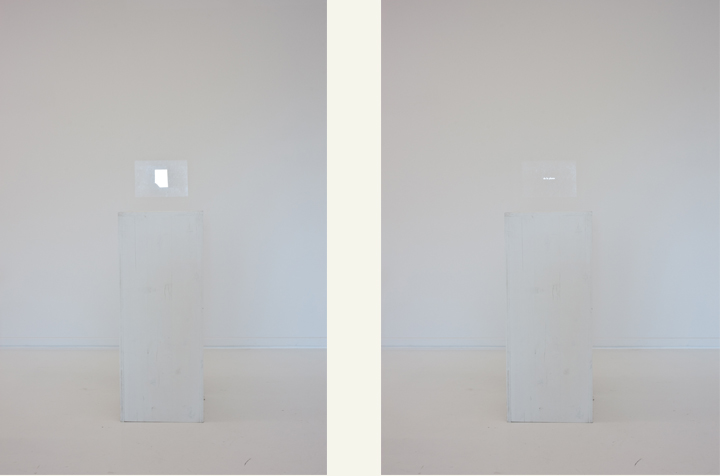

Ausstellungsansicht, Video: Distance in your eyes, Helmhaus Zürich, 2017

Videostill, Distance in your eyes, 2017

Detail view, Photo of me, Israel 1991

Distance in your eyes, 2017

Video, HD, 16:9, Zeitdauer 2‘ 52“, Loop, Farbe/ s/w, Ton

Im Video Distance in your eyes verbindet Françoise Caraco Fotos und Erinnerungen an ihren Besuch in Israel in den 1990er-Jahren mit der Videoaufnahme ihrer Busfahrt durch das heutige Jaffa. Zwischen Caracos Reisen liegen 20 Jahre und es treffen widersprüchliche Erzählweisen zu diesem Land aufeinander. Keine von diesen könnte durch eine andere letztlich ersetzt werden. Wenn Françoise Caraco den Reiserinnerungen ihres 19-jährigen Selbst begegnet, sind diese weiterhin gültig, wenn auch weit entfernt.

February 2015

February 2015Grandfathers Documents

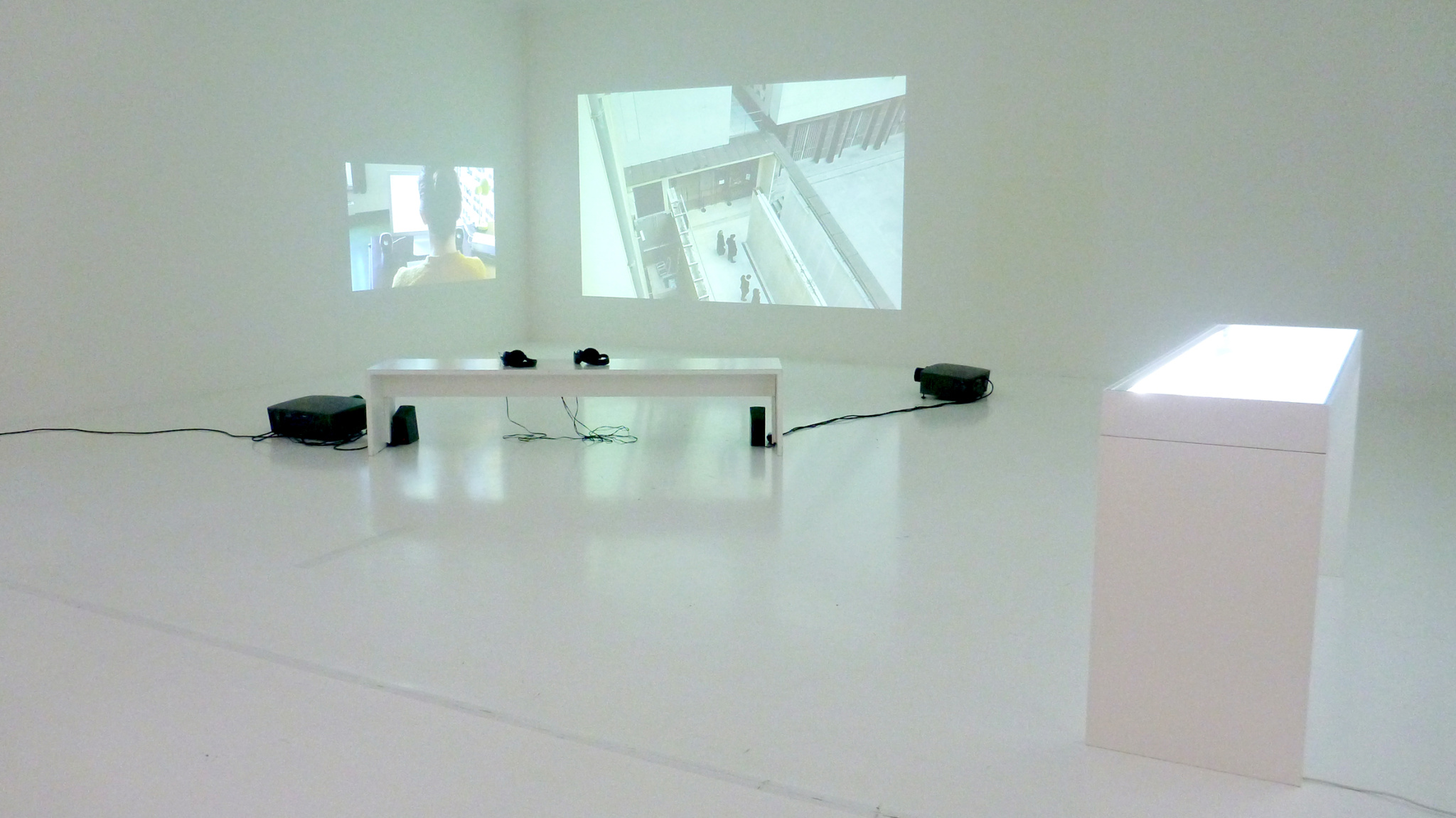

Exhibition view Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Detail, Doppelprojektion Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Exhibition view Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

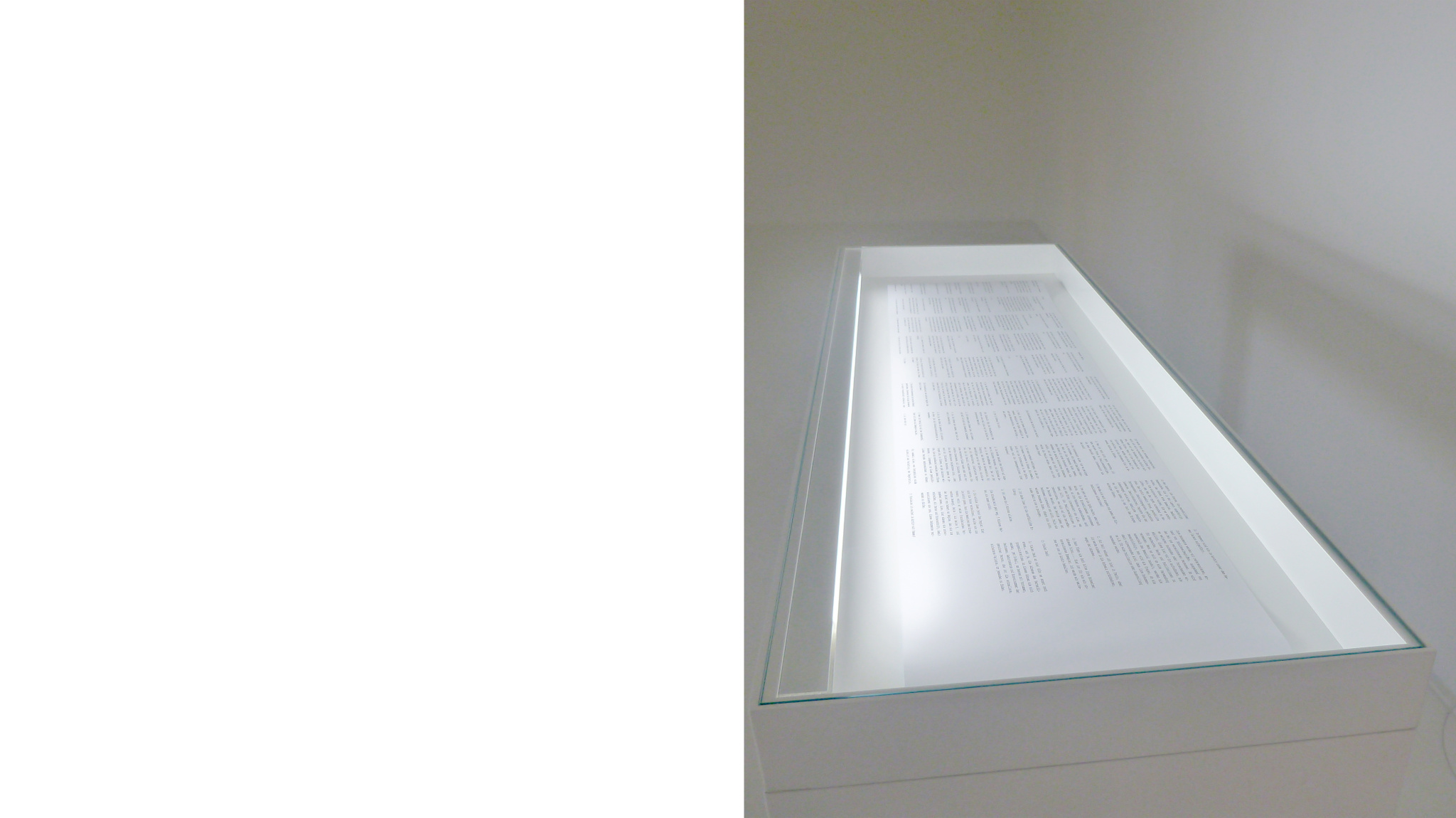

Detailansicht, Transkript, Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Audio work: Grossvaters Dokumente, 2015

Grossvaters Dokumente // Grandfathers Documents (2015)

Space installation, 2 Videoprojektionen, audiowork and transcript

Video, HD 16:9, 16'29''/ 20'23'', Audio work, 9'54'' spoken by Esther Becker

The ‘I’ in History.

The image would be the same. Were a historian to be filmed at work from behind it would probably look similar to the dual-channel video installation by Françoise Caraco: researching in front of the computer for sources, information, references that are then assembled to form a historical narrative. What, therefore, distinguishes an artist like Françoise Caraco from a historian? Precisely the fact that she films herself working, while a historian leaves the story he or she tells to speak for itself, or perhaps even allows themselves to become invisible behind it. Perhaps nowadays it is obvious that not only stories get authored, but that history itself does too – by ostensibly all-knowing narrators, from a specific perspective, with very definite interests. It comes as no surprise that history as a discipline is sometimes still taught as if its texts were engraved in stone, prescribed from a higher authority.

Françoise Caraco is on a par, if not better than a historian. A transcript of her encounter with a member of staff from a Paris archive dedicated to collecting source material on missing Jewish persons makes it apparent just how scrupulously Caraco undertook her search for her grandfather’s French relatives during her stay in France. The photographs and documents left by her grandfather have now become a part of the archive. Nevertheless, Caraco is not a historian. She recounts stories in the first person – in a text transmitted via headphones. In this narrative she herself passes the ‘mur des noms’ of the Mémorial de la Shoah – located directly opposite her temporary Paris studio, and which she likewise shows in her film footage – and reads the engraved names of the disappeared. And, importantly, she shows herself at work. The ‘I’ in Caraco’s form of history is written large.

Artists have learnt a lot from historians. But what can historians learn from artists? One example is that video – a predominant medium in this exhibition – can also serve to recount history. And that one can hide oneself behind a camera as easily as one can hide oneself behind an authoritarian authorship that excludes the first person. But there is nothing inevitable about this, as Françoise Caraco demonstrates in text and film.

Text: Daniel Morgenthaler for the exhibition Geschichten in Geschichte (Histories in History), curated by Daniel Morgenthaler, Helmhaus Zurich, 2015

July 2013

July 2013Family Photos I, II, III

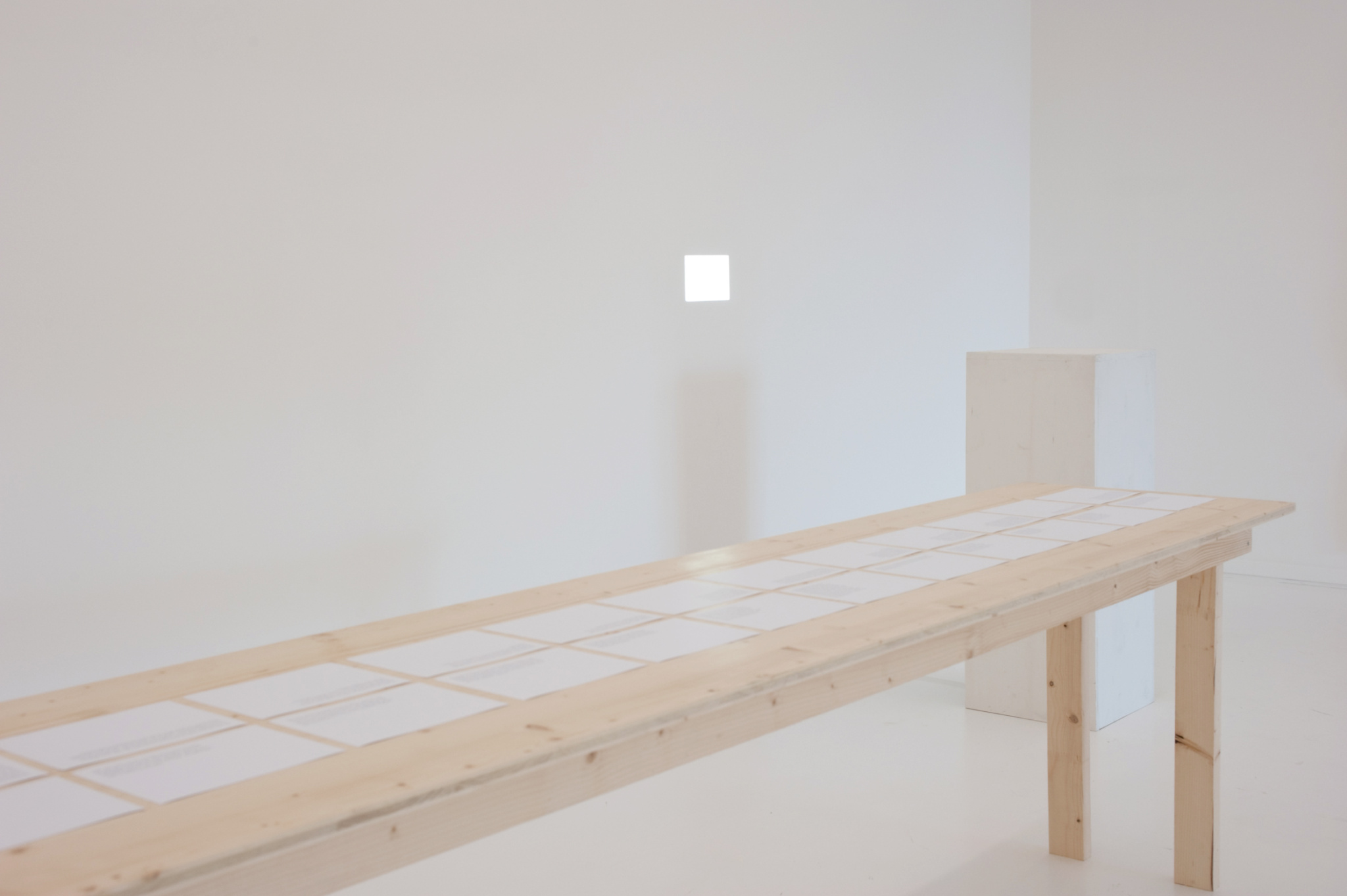

Exhibition view Familienfotos I,II, III, in the group show Stipendien- und Atelierwettbewerb, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detail view: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detail view: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detail view: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detail view: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Audio work: Familienfotos III, 5' 32'' , by loop

Ausschnitt Video: Familienfotos I, HD 16:9, 2:33 min

Familienfotos I, II, III – Family Photos I, II, III (2013)

I: Video projection, HD 16:9, time 2' 33", in loop

II: 26, A5 filing cards, laser-print on paper

III: Audio work, time 5' 30", loop, speaker Esther Becker

Françoise Caraco tackles the story of her grandfather’s life. In the process, the absorbing of her own personal family history represents a gesture of connection: it serves her as an opportunity to reconstruct and reflect on the public and political circumstances of a bygone era. In the work Familenfotos, Françoise Caraco constructs an experimental layout of familial and social belonging and broaches the subject of the demarcations involved. To do so she uses portrait pictures and fragments of information from letters from 1904 to 1942 kept by her grandfather, the son of a Sephardic-Jewish immigrant from Istanbul.

Family Photos is a spatial installation in which Françoise Caraco stages a collection of photos and text fragments inherited from her grandfather. From her own contemporary perspective Caraco repeats her grandfather's attempts, based on family photos and written documents, to ascertain the presence of his relatives. The basis materials for Caraco are photographs, postcards and letters that relatives sent from their respective new ‘home countries’. In Caraco’s presentation these items become historic documents, revealing less about the concrete life situations of the family and instead posing more questions about public states-of-mind as seen from an intimate perspective.

The artist has taken the available and patchy archive material from the early twentieth century, carefully reviewed it, interpreted the content and formally transformed it. The customary black-and-white family portraits from the epoch have been translated into short texts in which she tries to descriptively reconstruct the interrelations between the depicted people themselves and with the simultaneously transported contexts. Caraco deploys an actress to read aloud the written details of the dates and locations derived from the respective pictures in the form of a mundane list. The empty reverse sides of the photos on which family members are shown are transformed by the artist into abstract pictures, projected in sequence with textual fragments from the written correspondence onto a wall. Using these three forms of translation Caraco reconstructs links and correlations that generate a new present-day image of the past. At the same time the blank reverses and the fragmented texts indicate losses and voids.

Familienfotos queries the medium of photography in the widest possible sense as a form of documentation. What can photography transport and how? What are its claims to truthfulness and its possibilities? Caraco understands a photograph as a document that is not always readily legible. As such, to begin with she found the photographs left by her grandfather indecipherable. She was unable to either recognise or sort the people depicted. Based on the identical source material, in an attempt to make it decipherable Caraco evolved three different forms of translation that endow the fleeting documents with a new coherence. Whether a private past can be reconstructed from these translations remains moot – the question being whether the product is not simply a construed reality, a fiction. It is precisely at this crux that we are re-confronted with a paradox expressed by Hito Steyerl: ‘Doubts as to their truth-value do not make documentary images weaker, rather stronger.’

Text: Irene Grillo, 2013