Dezember 2023

Dezember 2023Zofinger Luft (ausgewählte Werke)

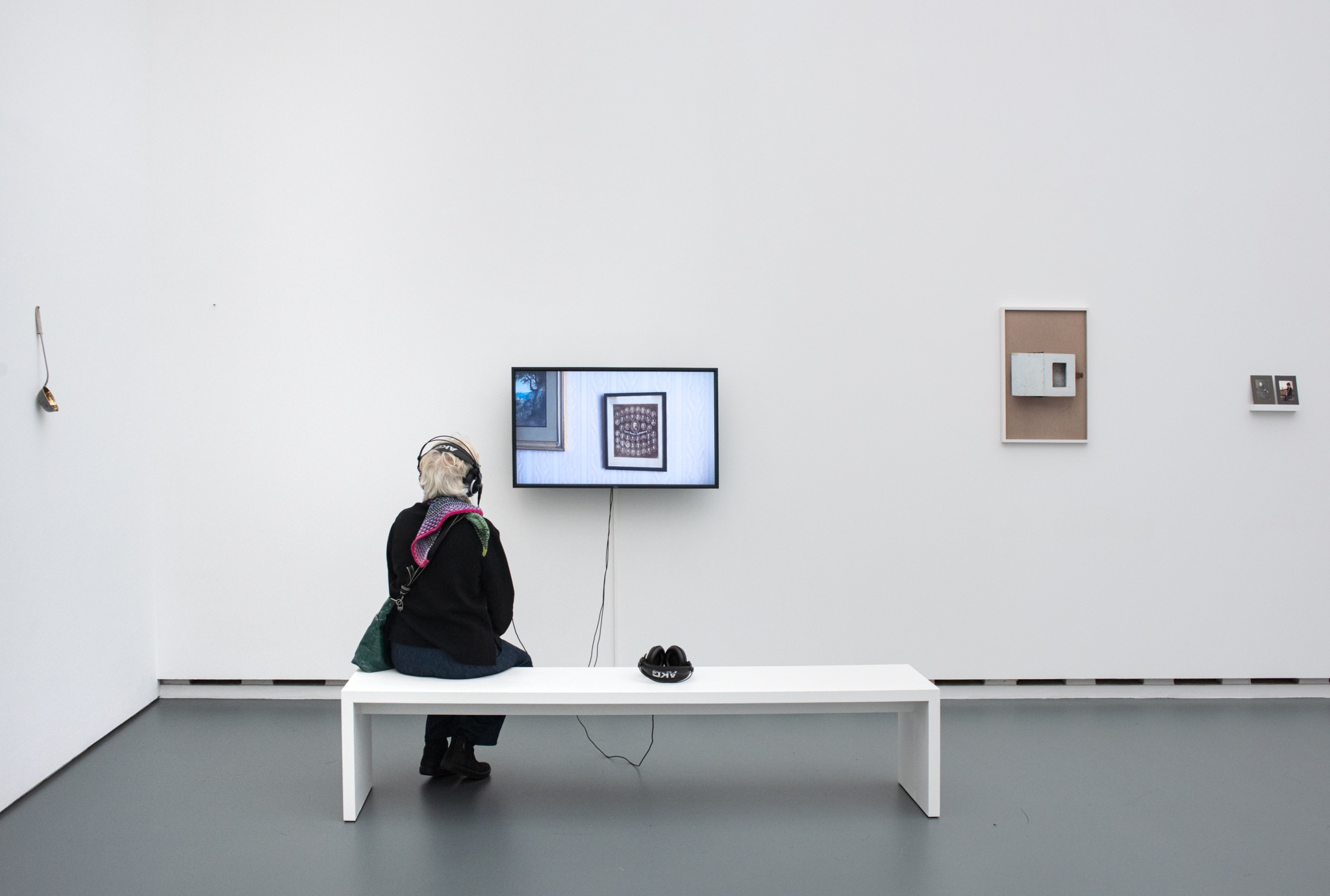

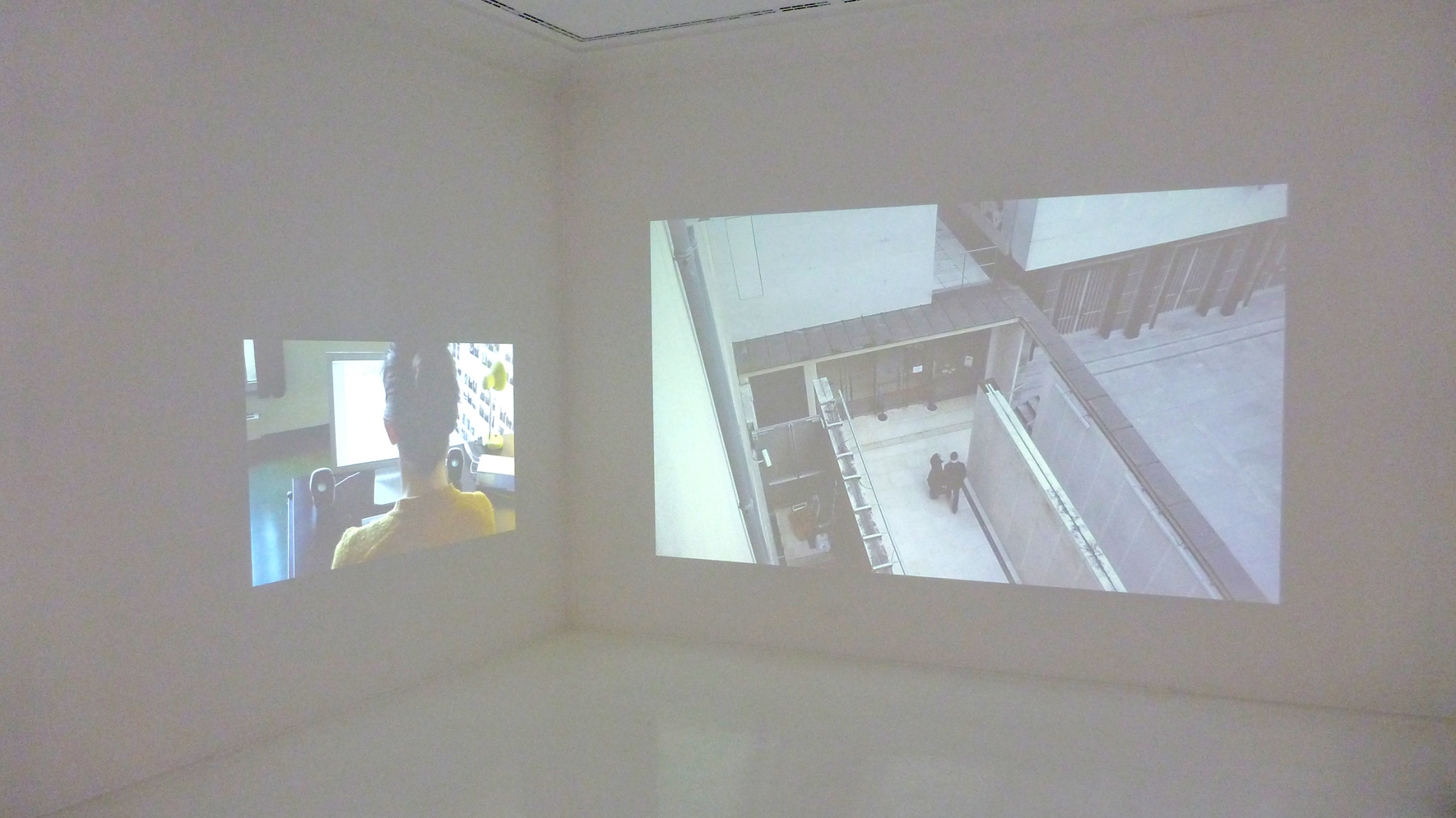

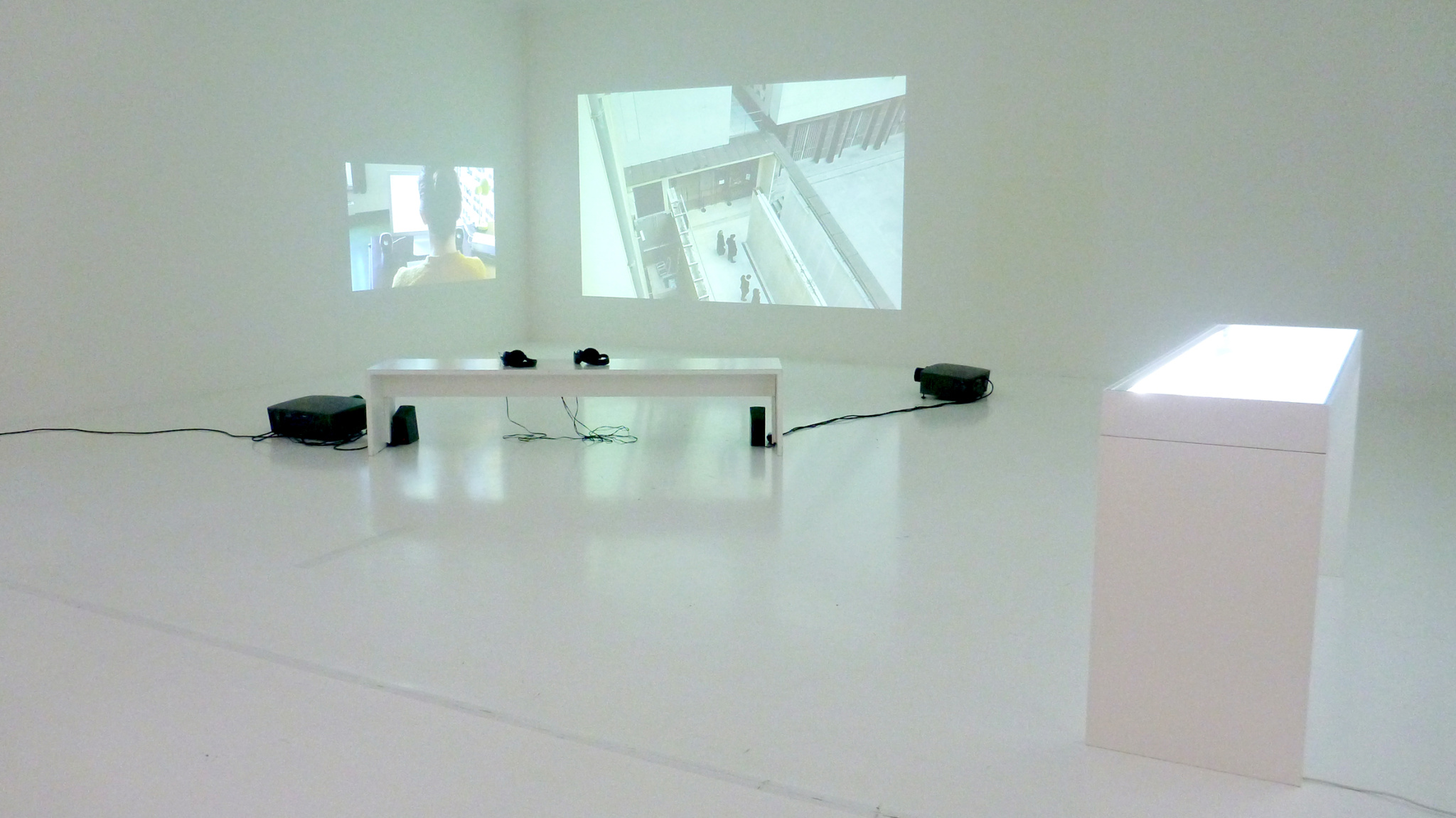

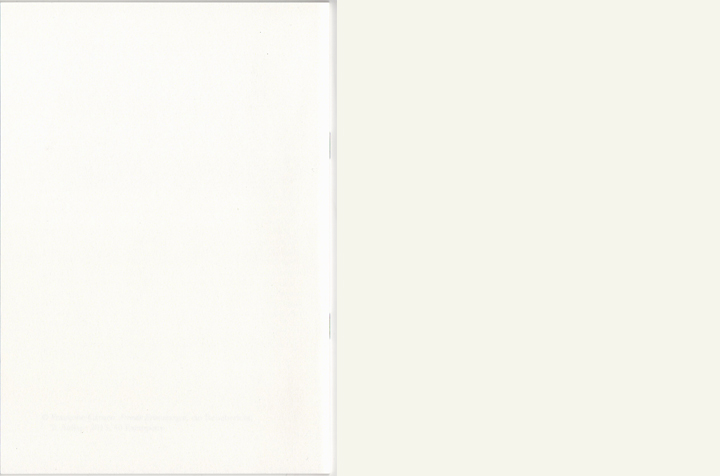

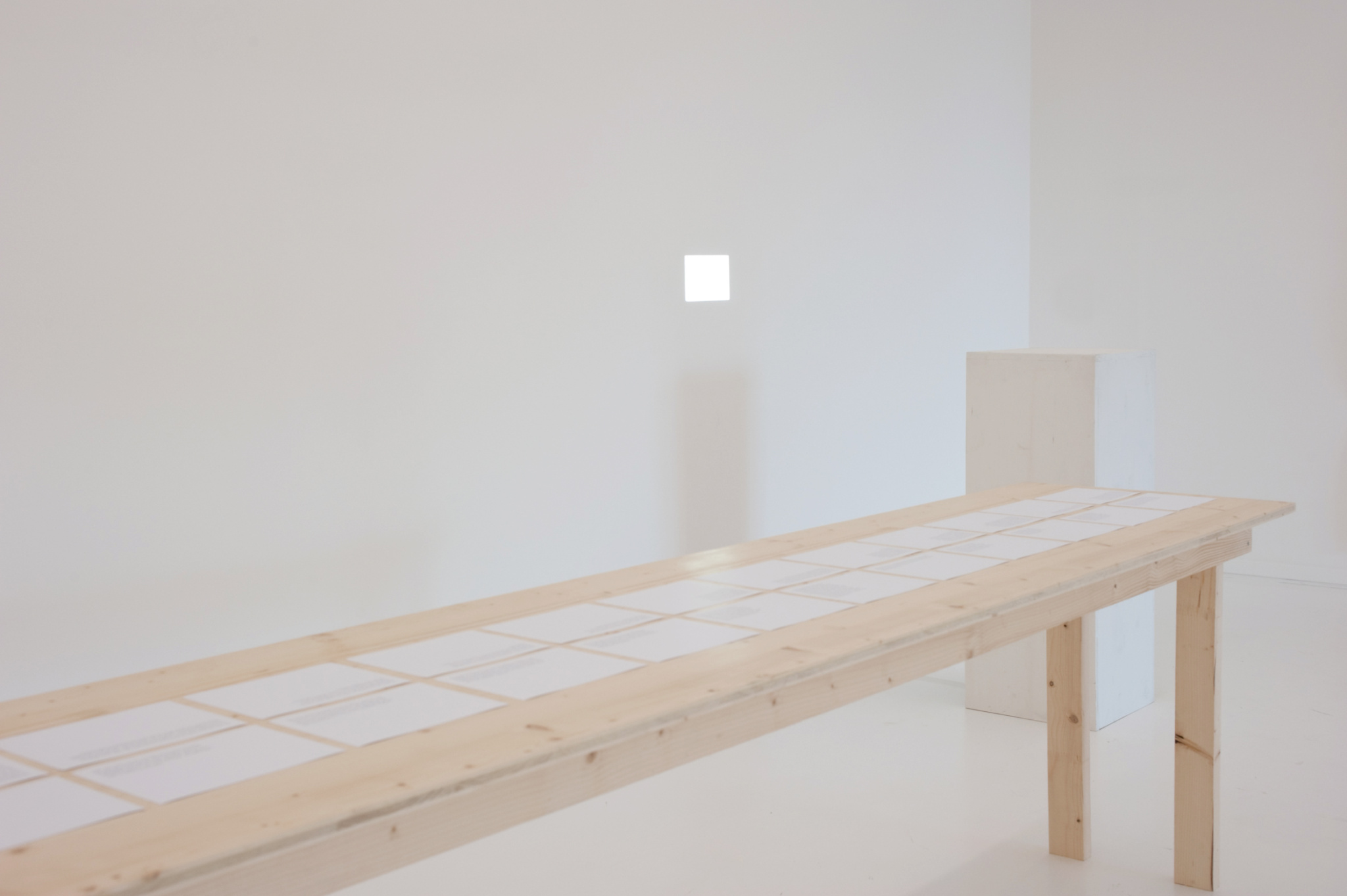

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023, Foto: Caroline Minjolles

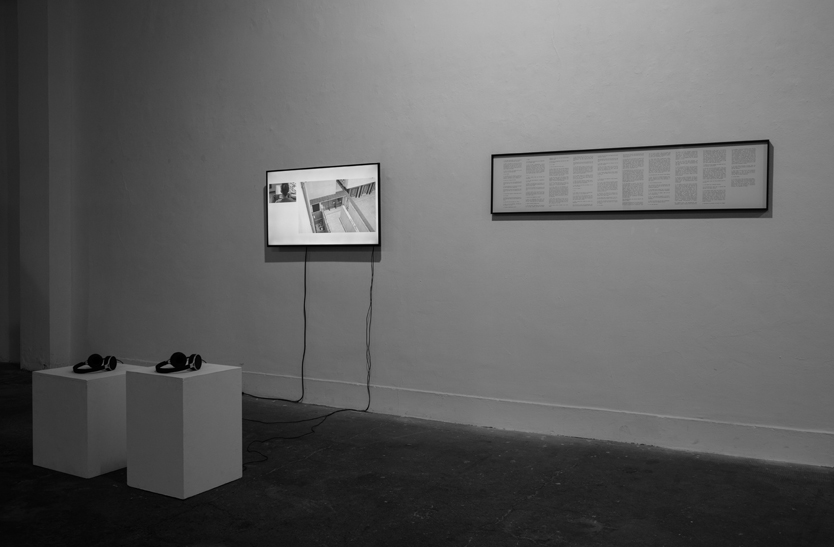

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

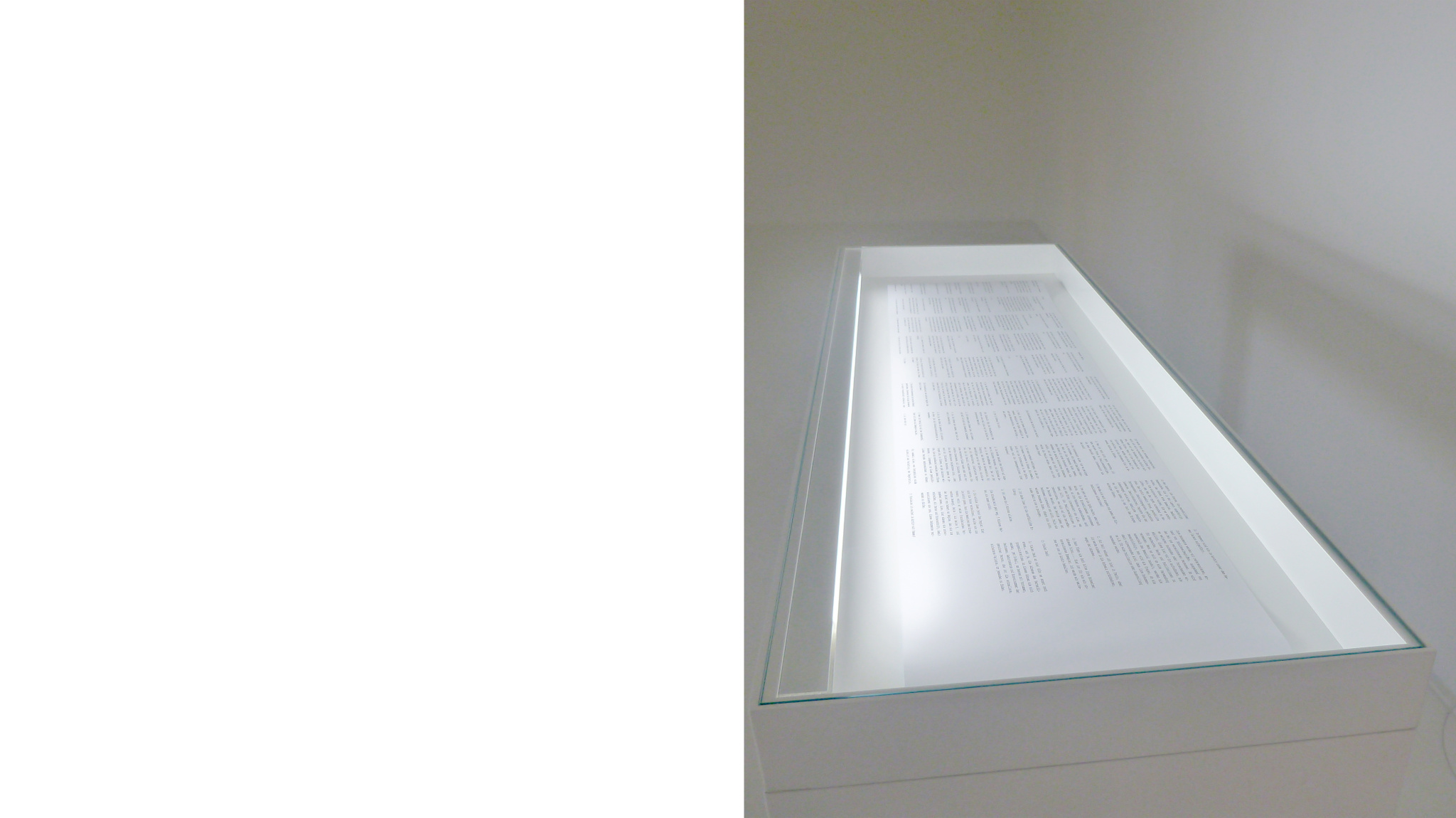

Detailansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

Detailansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

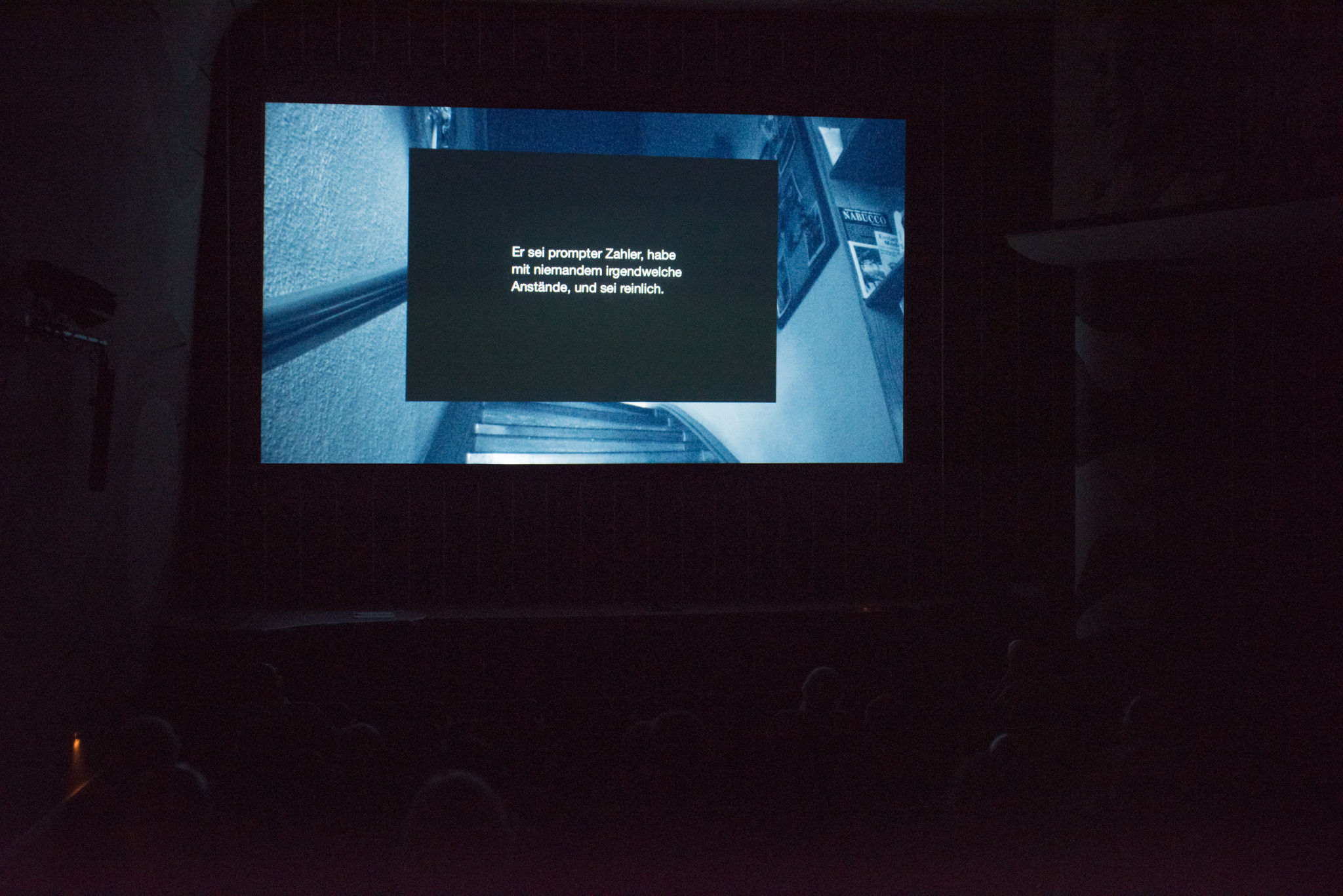

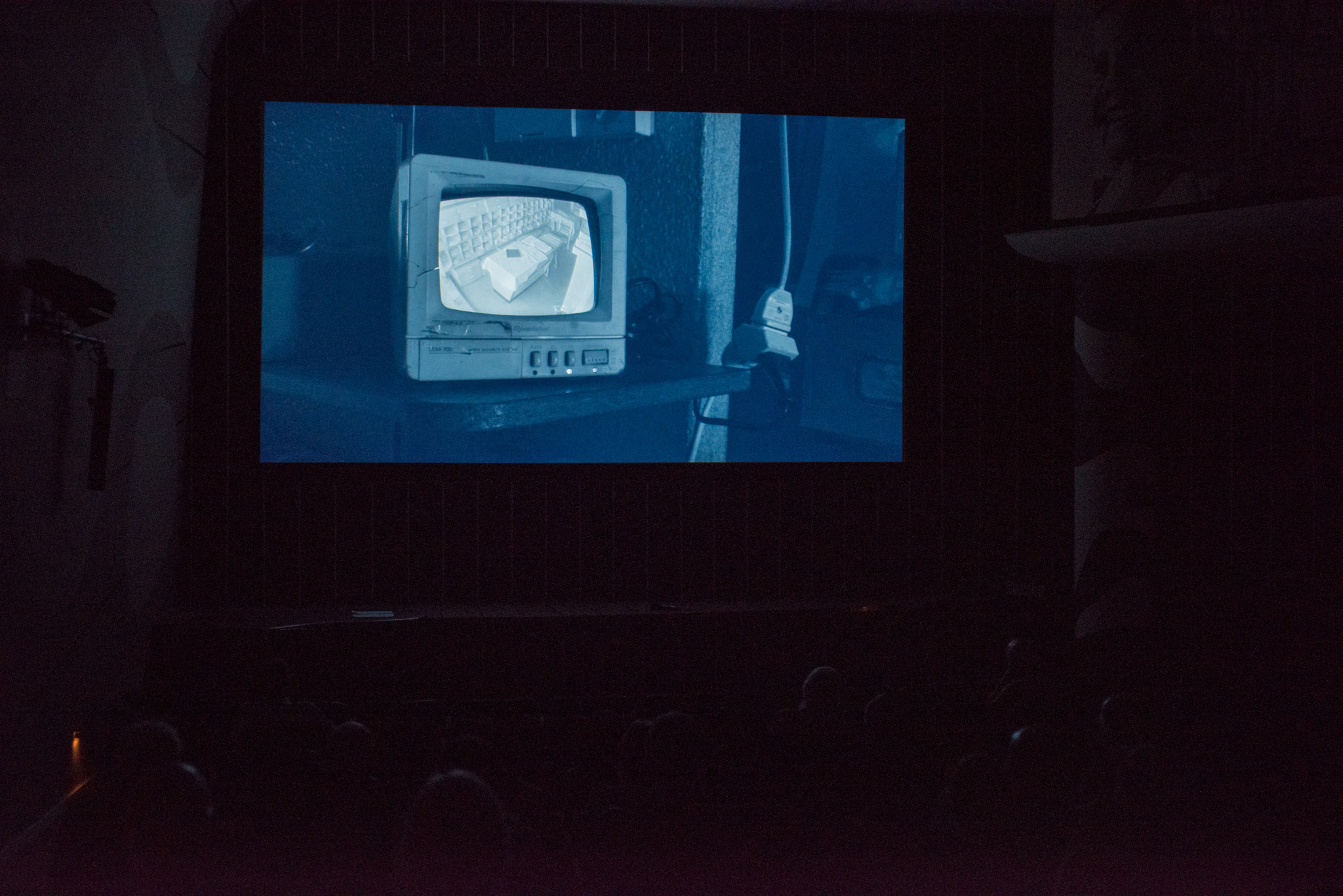

Videostill, Zofinger Luft 1878 - 1892, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

Videostill, Zofinger Luft 1878 - 1892, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

Videostill, Zofinger Luft 1878 - 1892, in der Gruppenausstellung, Auswahl 23, Aargauer Kunsthaus, 2023

8 x Fotografien: Inkjetdruck auf Innovapapier, 118 x 80 cm, 60 x 40 cm, 87 x 60 cm, 45 x 30 cm, 15 x 10.8 cm

1 x Video: HD 16:9, 1920 x 1080, Farbe, 9:52, Ton

1 x Silberner Suppenlöffel

1 x Ausgestopfter Rabe

Für die "Auswahl 23" im Aargauer Kunsthaus habe ich einen Teil meiner mehrteiligen Arbeit ZOFINGER LUFT ausgestellt, welche im Frühling 2023 in der Gruppenausstellung “Mindmapping Art” im Kunsthaus Zofingen gezeigt wurde.

In dieser Arbeit recherchiere ich zu meiner Urgrossmutter Clara Bollag und deren Familie, im Zusammenhang mit der Ortsgeschichte Zofingens. Clara Bollag hatte seit ihrer Geburt 1884 in Zofingen gelebt, bevor sie 1904 zum Ursprungsort ihrer Familie, nach Endingen zog. Auf den Spuren meiner Urgrossmutter besuchte ich das Museum Zofingen, die Bibliothek und das Stadtarchiv Zofingens, recherchierte im Archiv des Turnvereins Zofingens, führte Gespräche mit Bewohner*innen und suchte nach Spuren meiner jüdischen Vorfahren.

Das Resultat dieser Recherche ist eine mehrteilige Installation, welche sich aus Fotografien, einem Video, persönlichen Objekten aus dem Nachlass meiner Familie, sowie Fundstücke aus dem Musuem Zofingens zusammensetzt.

August 2023

August 2023Durchfluten

Detailansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Detailansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Austellungsasicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Detailansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Detailansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Audiostück + Ausstellungsansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Durchfluten, in der Gruppenausstellung, Flow Edition, Ancienne Synagogue Hégenheim, 2023

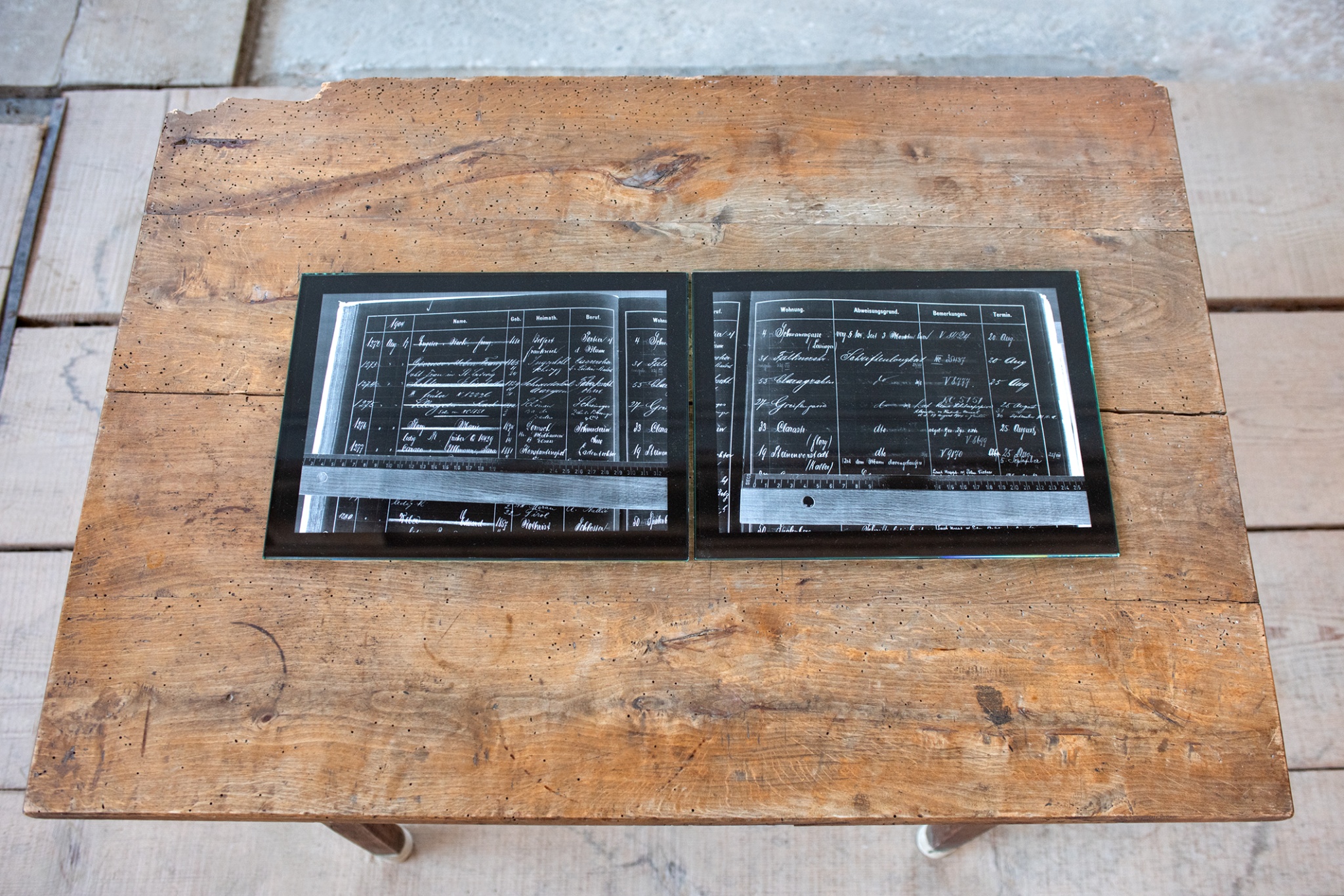

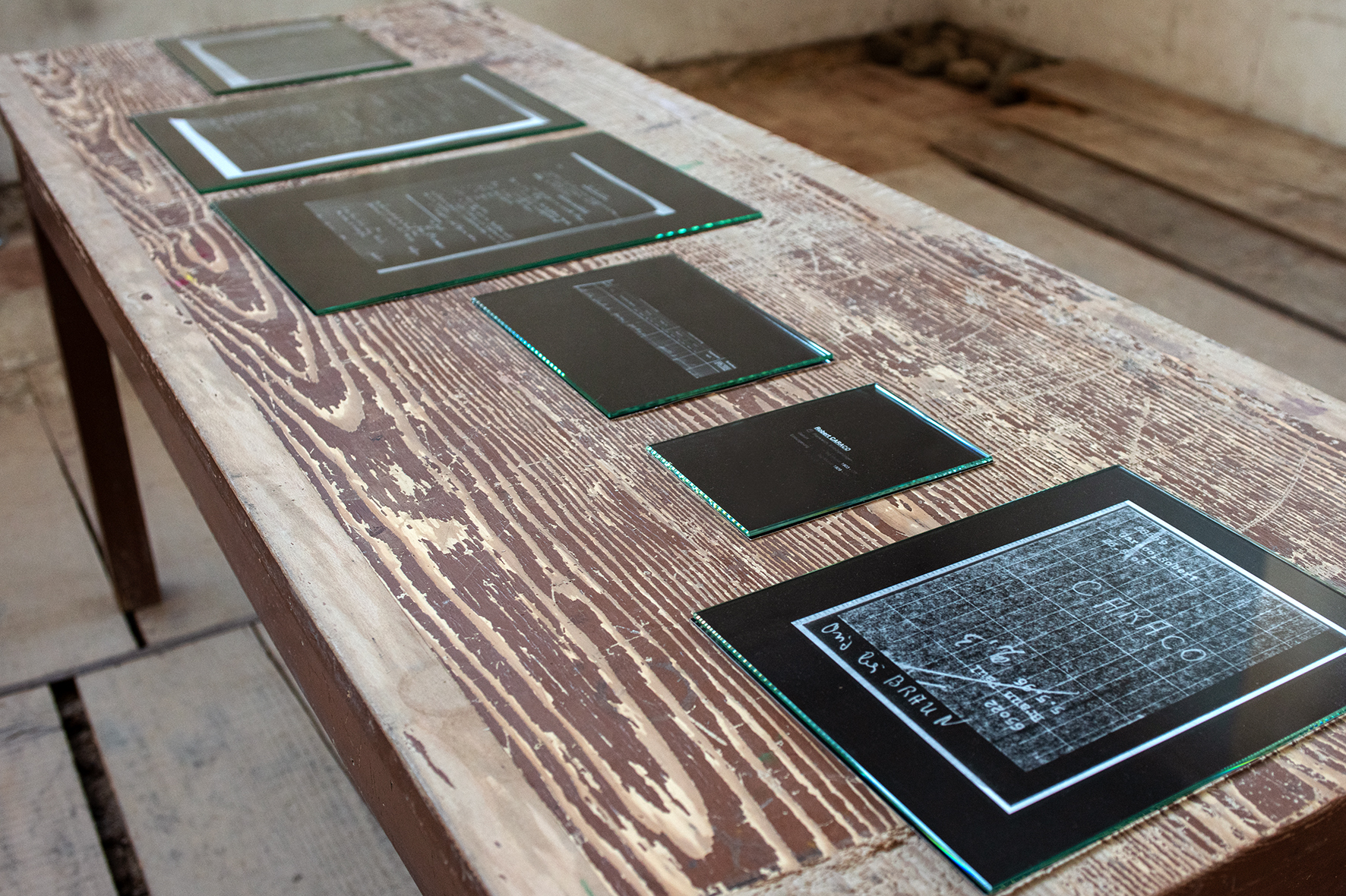

Fotogramme auf Barytpapier, hinter Glas, Grössen variabel:

30.5 x 40.6 cm; 24 x 30.5 cm, 17.8 x 24 cm, 12.7x 17.8 cm

In der Installation stehen vier abgenutzte Holztische, welche die Künstlerin vor Ort in der Synagoge gefunden hat. Sie stehen in einer Gruppe, wie in einem Archiv oder einer Bibliothek. Auf den Tischen liegen Abbilder von amtlichen Dokumenten, ausgeschnitten und unter Glasplatten platziert.

Für die Arbeit «Durchfluten» hat Françoise Caraco das Recherchematerial, welche sie in verschiedenen Archiven gefunden hat, auf Fotopapier gelegt und durchleuchtet. Auf den entstandenen Fotogrammen heben sich die spärlichen Überlieferungen zu ihrer Familiengeschichte ab wie Licht vom Dunkel.

Der Ausgangspunkt der Recherche zu ihrer Familiengeschichte, verbindet Françoise Caraco spezifisch mit dem Ort Hegenheim. Ihr Urgrossonkel, eingewanderter Jude aus Konstantinopel, war einmal mit einer Jüdin aus Hegenheim verheiratet. Die Spuren dieser Familiengeschichte, sowie des gemeinsamen Sohnes Robert Caraco führten unter anderem nach Basel, Zürich, Frankreich, sowie nach Buchenwald, Natzweiler, Dachau und wieder zurück. Ihre Fundstücke - zu Geburt, Aufenthalt, Heirat, Einbürgerung oder Streitigkeiten, Inventare, Listen - was sie über ein persönliches Schicksal verraten oder eben auch nicht zu sagen vermögen, beinhalten jedoch auch immer Leerstellen. Diese Leerstellen zeichnet Françoise Caraco mit eigenen Fragen nach und verwebt sie mit dem Archivmaterial zu einer Geschichte. Diese können Besuchende als Audiospur auf einem Stuhl sitzend und durch das grosse Fenster an der Stirnseite des Raumes blickend hören. Hörend empfinden wir den Weg der Künstlerin und ihrer Recherchen nach, begeben uns auf eine Zeitreise in unterschiedliche Welten und holen durch das Fenster blickend, das Draussen in Gedanken in den Raum hinein.

Seit einigen Jahren beschäftigt sich Françoise Caraco in ihren ortsspezifischen Installationen mit der eigenen Familiengeschichte. Dabei nimmt sie wiederholt die hinterlassenen Notizen ihres Grossvaters als Grundlage und sucht durch die Kunst, die Lücken zu füllen.

Text: Patricia Hujinen

Audiostück, Durchfluten, 15' 18'', 2023

Gesprochen von Alma Caraco

April 2023

April 2023Zofinger Luft

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023, Foto: Rachel Bühlmann

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023, Foto: Rachel Bühlmann

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Detailansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Ausstellungsansicht, Zofinger Luft, in der Gruppenausstellung, Mindmapping Art, Kunsthaus Zofingen, 2023

Fotografien: Inkjetdruck auf Innovapapier, 118 x 80 cm, 60 x 40 cm, 87 x 60 cm, 45 x 30 cm

Video: HD 16:9, 1920 x 1080, Farbe, 9:52

Besucherinnen und Besucher werden von der vielteiligen Installation von Françoise Caraco empfangen, die sich über zwei Stockwerke verteilt. Caracos Installation mit dem Titel: ZOFINGER LUFT ist eine Auseinandersetzung mit ihrer eigenen Familiengeschichte. Caraco recherchiert zum Leben ihrer Urgrossmutter Clara Bollag und deren Familie im Zusammenhang mit der Ortsgeschichte von Zofingen. Clara Bollag lebte seit ihrer Geburt 1884 mit ihrer Familie in Zofingen, bevor sie 1892 zum Ursprungsort ihrer Familie, nach Endingen zog. Auf den Spuren Clara Bollags besuchte Françoise Caraco die Bibliothek und das Stadtarchiv in Zofingen, recherchierte im Archiv des Turnvereins Zofingen, im Museum Zofingen und dessen historischen und naturhistorischen Abteilung und führte Gespräche mit Bewohner*innen. Sie suchte nach Spuren ihrer Vorfahren, die jüdischer Herkunft waren. Bei ihrer Recherche erfuhr die Künstlerin, dass Clara Bollags Vater Viehhändler gewesen war, damals eine der wenigen beruflichen Möglichkeiten für Juden. Seine Frau und er lebten mit der Familie an verschiedenen Adressen in der Oberstadt Zofingens. Bollags Viehstall befand sich an der Scheunengasse. Diese Informationen hat Françoise Caraco im Register der Einwohnerkontrolle Zofingen 1898, im Geburtsregister a II, 1883-1891, im Liegenschaftsverzeichnis der Gemeinde-Zofingen von 1886 oder im Steuerbuch der Gemeinde Zofingen 1892-1897 gefunden. Daraus lässt sich auf die Lebensumstände der Familie Bollag schliessen, doch ergibt sich kein Bild, wie ihre Urgrossmutter Clara in Zofingen lebte.

Was mochte die Familie von Clara Bollag 1892 zur Rückkehr nach Endingen bewogen haben? Wo und wie lebte Clara Bollag? Vieles bleibt unbeantwortet. Diese fehlenden Informationen zeichnet Françoise Caraco anhand von bildlichen Leerstellen in der Installation ZOFINGER LUFT nach. Sie visualisiert die Leerstellen einerseits mit Löschblättern welche sie in den Büchern des Stadtarchivs Zofingen gefunden hat, andererseits mit präparierten Vögeln, die in der Zeit von Clara Bollag in Zofingen gelebt haben und die sie fotografiert oder mit unbelichteten Fotonegativplatten, aus dem Nachlass eines Zofinger Fotografen, welche thematisch in Zusammenhang mit der Geschichte der Familie stehen. Finale der Installation bildet das Videowerk: ZOFINGER LUFT, 1878 – 1892, das in bewegtem Bild und gesprochenem Wort die künstlerische Recherche von Françoise Caraco zu Clara Bollag vereint.

Text: Eva Bigler

Dezember 2022

Dezember 2022Hidden Istanbul

Ausstellungsansicht, Hidden Istanbul, in der Gruppenausstellung, Prix Photoforum 2022, Pasquart Photoforum, Biel, 2022, Foto: Aline Bovard Rudaz

Ausstellungsansicht, Hidden Istanbul, in der Gruppenausstellung, Prix Photoforum 2022, Pasquart Photoforum, Biel, 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Hidden Istanbul, in der Gruppenausstellung, Prix Photoforum 2022, Pasquart Photoforum, Biel, 2022

Detailansicht, Hidden Istanbul, in der Gruppenausstellung, Prix Photoforum 2022, Pasquart Photoforum, Biel, 2022, Foto: Aline Bovard Rudaz

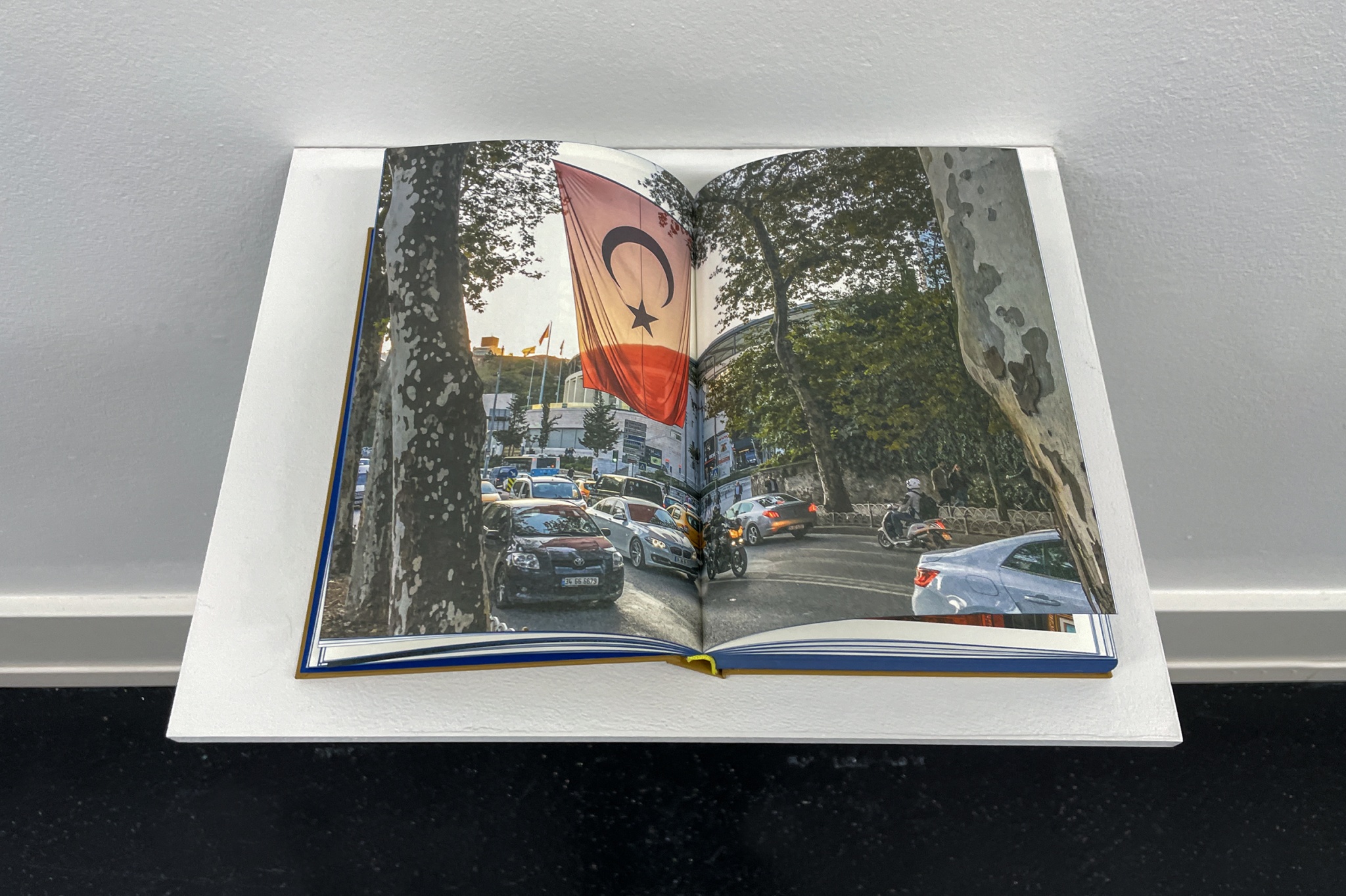

Detailansicht, Buch: Hidden Istanbul, in der Gruppenausstellung, Prix Photoforum 2022, Pasquart Photoforum, Biel, 2022

Fotografien: Inkjetprint auf gmg ProofMedia Newspaper 76g, Grösse: 77.3 x 58 cm oder 43.5 x 58 cm

Buch: Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

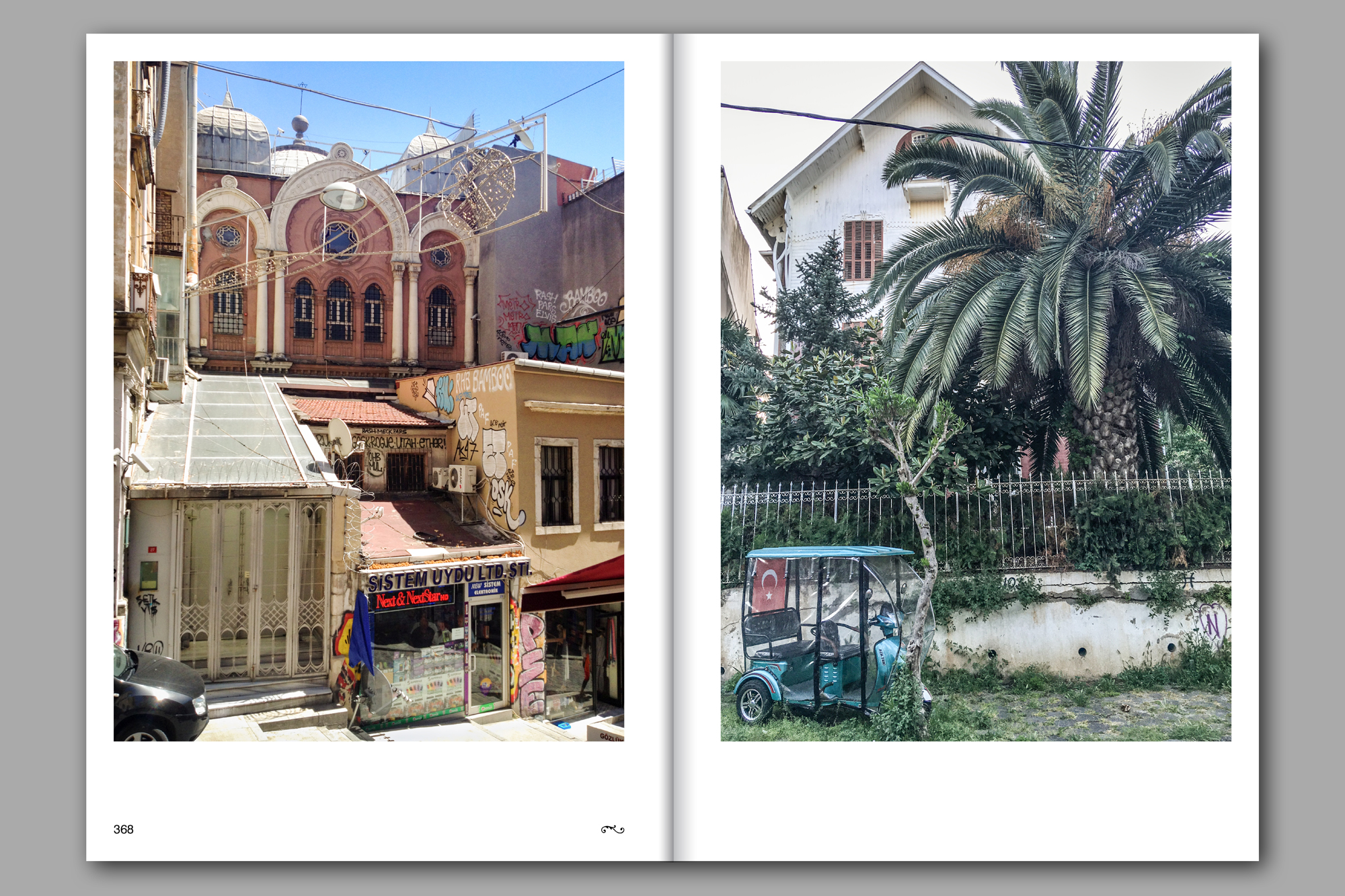

Wie kann etwas dargestellt, gezeigt werden, das versteckt ist? Françoise Caraco hat mit der vorliegenden Pu-blikation HIDDEN ISTANBUL ebendiesen Versuch unter-nommen. Auf der Suche nach ihren Vorfahren reiste Françoise Caraco mehrfach nach Istanbul und hat mit Menschen gesprochen, die eine*n Caraco – oder Karako – kennen oder gekannt haben oder sich zumindest an diesen Namen erinnerten. Ihr bot sich ein einzigartiger Einblick in die jüdische Kultur der Sephardim. Diese bewohnen die türkische Metropole Seit Jahrhunderten, was aber den Augen der meisten verborgen bleibt.

In HIDDEN ISTANBUL verwebt Françoise Caraco Fami-lienerinnerungen feinfühlig mit ihren eigenen, zeitge-nössischen Fotografien der Reise und Recherche. Dazwi-schen lässt sie unterschiedliche Stimmen der jüdischen Gemeinde Istanbuls zu Wort kommen. Das Ergebnis ist ein reichhaltiges, nuanciertes Porträt der verschwindenden Vergangenheit und der immer noch lebendigen Gegenwart der Stadt aus der Perspektive eines

September 2022

September 2022Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Ausstellungsansicht, Gizli Istanbul / Hidden Istanbul, Schneidertempel Arts Center, Istanbul 2022

Inkjetprint auf gmg ProofMedia Newspaper76g, 77.3 x 58 cm oder 43.5 x 58 cm

Buch: Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Das Buch HIDDEN ISTANBUL dient als Grundlage für die Ausstellung im Schneidertempel Arts Center. Fotografien und Abbildungen von Archivmaterial werden im Inkjet-Verfahren auf dünnes Zeitungspapier gedruckt und gleichermaßen als eine Art dokumentarische Spurensuche des jüdischen Lebens in Istanbul an die Wände gehängt. Die Aussagen der Interviewpartner sind im Buch zu finden.

Wie kann etwas dargestellt, gezeigt werden, das versteckt ist? Françoise Caraco hat mit der vorliegenden Pu-blikation HIDDEN ISTANBUL ebendiesen Versuch unter-nommen. Auf der Suche nach ihren Vorfahren reiste Françoise Caraco mehrfach nach Istanbul und hat mit Menschen gesprochen, die eine*n Caraco – oder Karako – kennen oder gekannt haben oder sich zumindest an diesen Namen erinnerten. Ihr bot sich ein einzigartiger Einblick in die jüdische Kultur der Sephardim. Diese bewohnen die türkische Metropole Seit Jahrhunderten, was aber den Augen der meisten verborgen bleibt. In HIDDEN ISTANBUL verwebt Françoise Caraco Fami-lienerinnerungen feinfühlig mit ihren eigenen, zeitge-nössischen Fotografien der Reise und Recherche. Dazwi-schen lässt sie unterschiedliche Stimmen der jüdischen Gemeinde Istanbuls zu Wort kommen. Das Ergebnis ist ein reichhaltiges, nuanciertes Porträt der verschwindenden Vergangenheit und der immer noch lebendigen Gegenwart der Stadt aus der Perspektive eines weitgehend unbe-kannten Teils ihrer Bevölkerung.

Dezember 2021

Dezember 2021Hidden Istanbul

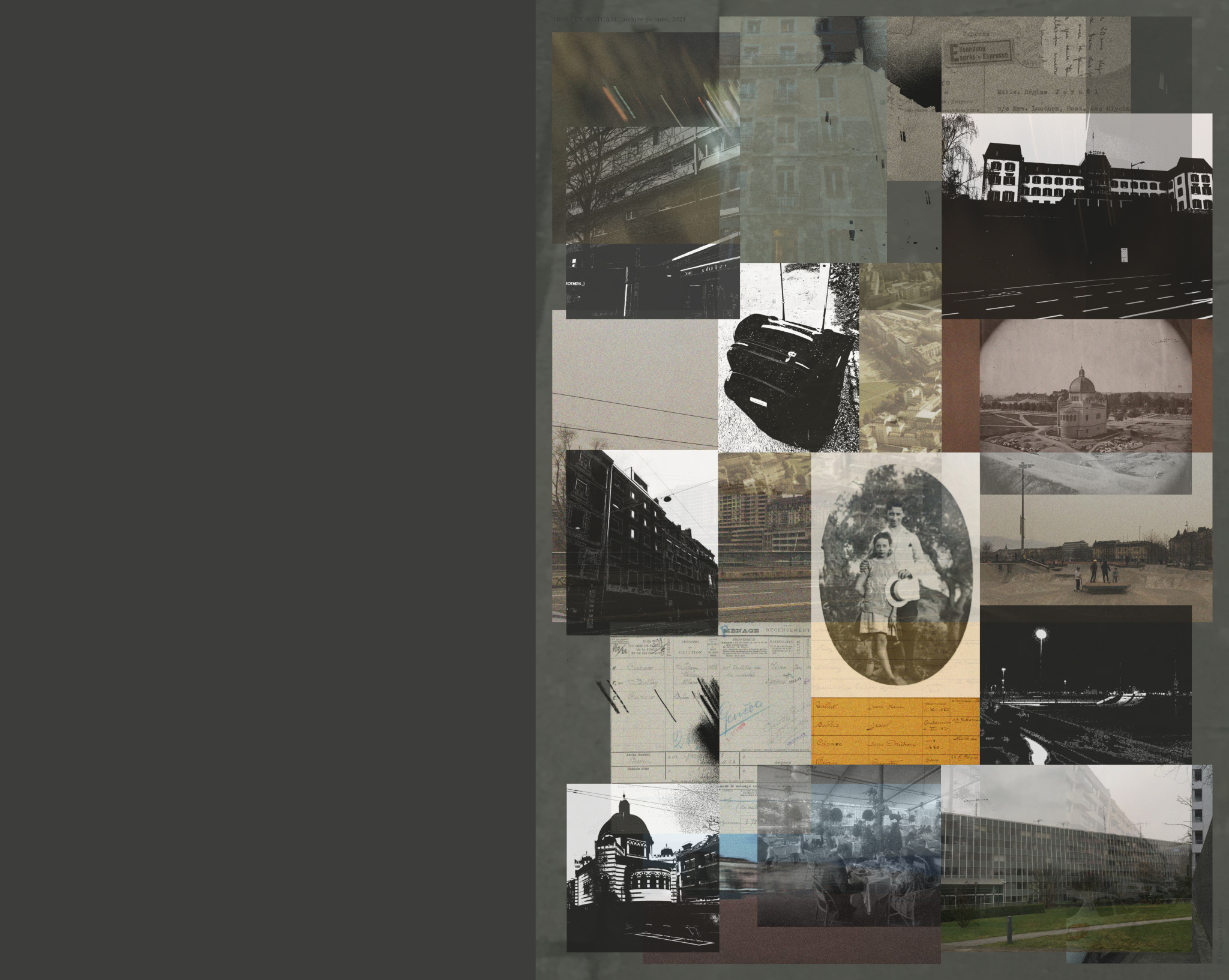

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hidden Istanbul, APE#194, Poster, Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021

Hardcover 17 × 24 cm, 404 Seiten, 263 Farbfotografien, Sprache: Englisch, ISBN 9789493146716

Design & Editing: Lien Van Leemput & Françoise Caraco

Design: Lien Van Leemput & Françoise Caraco for 6'56" Art Paper Editions, Belgien, 2021.

Jedem Buch ist ein zweiseitiges Poster beigefügt.

Wie kann etwas dargestellt, gezeigt werden, das versteckt ist? Françoise Caraco hat mit der vorliegenden Publikation Hidden Istanbul ebendiesen Versuch unternommen. Auf der Suche nach ihren Vorfahren reiste Françoise Caraco mehrfach nach Istanbul und hat mit Menschen gesprochen, die eine*n Caraco – oder Karako – kennen oder gekannt haben oder sich zumindest an diesen Namen erinnerten. Ihr bot sich ein einzigartiger Einblick in die jüdische Kultur der Sephardim. Diese bewohnen die türkische Metropole Seit Jahrhunderten, was aber den Augen der meisten verborgen bleibt.

In Hidden Istanbul verwebt Françoise Caraco Familienerinnerungen feinfühlig mit ihren eigenen, zeitge-nössischen Fotografien der Reise und Recherche. Dazwischen lässt sie unterschiedliche Stimmen der jüdischen Gemeinde Istanbuls zu Wort kommen. Das Ergebnis ist ein reichhaltiges, nuanciertes Porträt der verschwindenden Vergangenheit und der immer noch lebendigen Gegenwart der Stadt aus der Perspektive eines weitgehend unbekannten Teils ihrer Bevölkerung.

März 2021

März 2021Trolley Suitcase

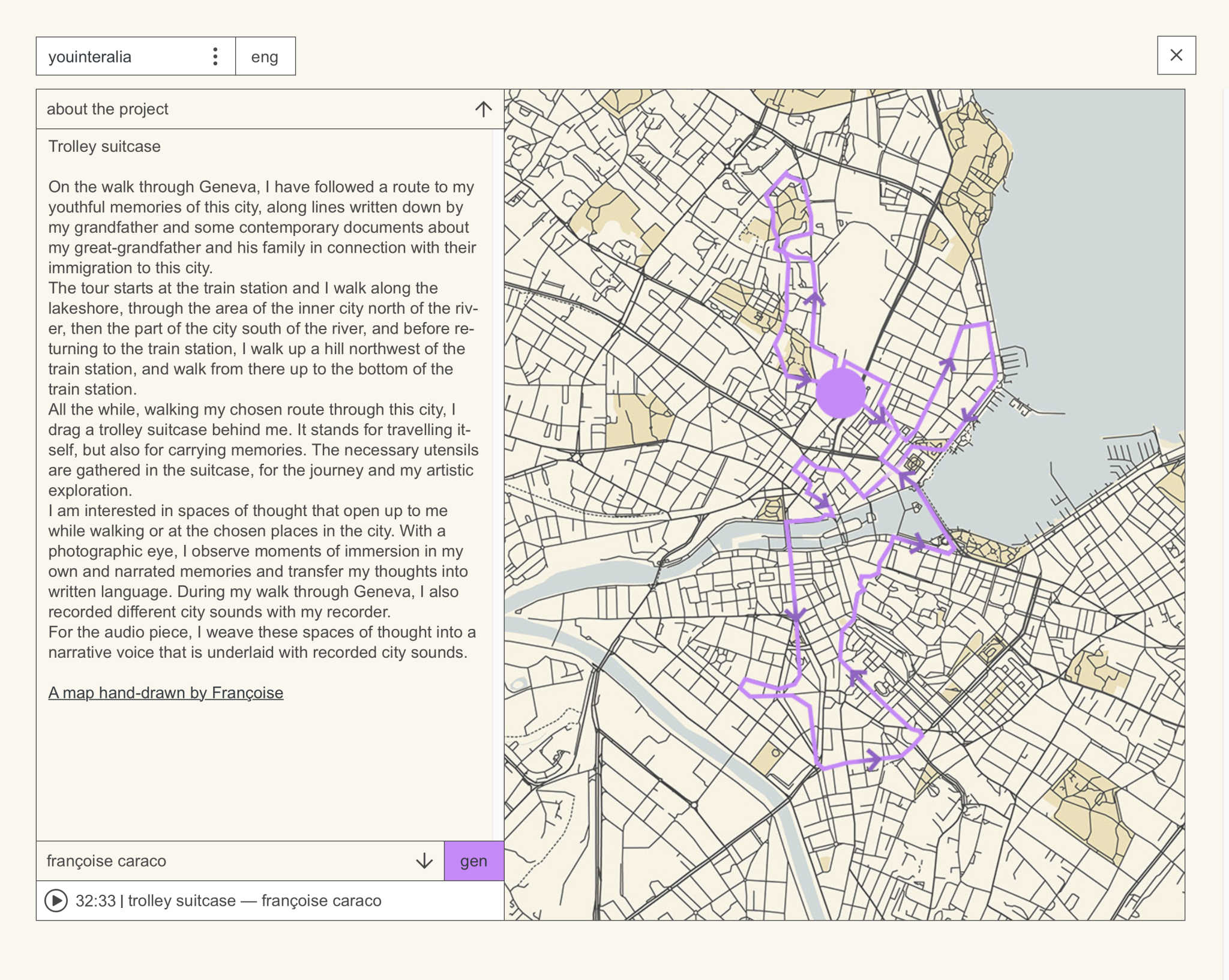

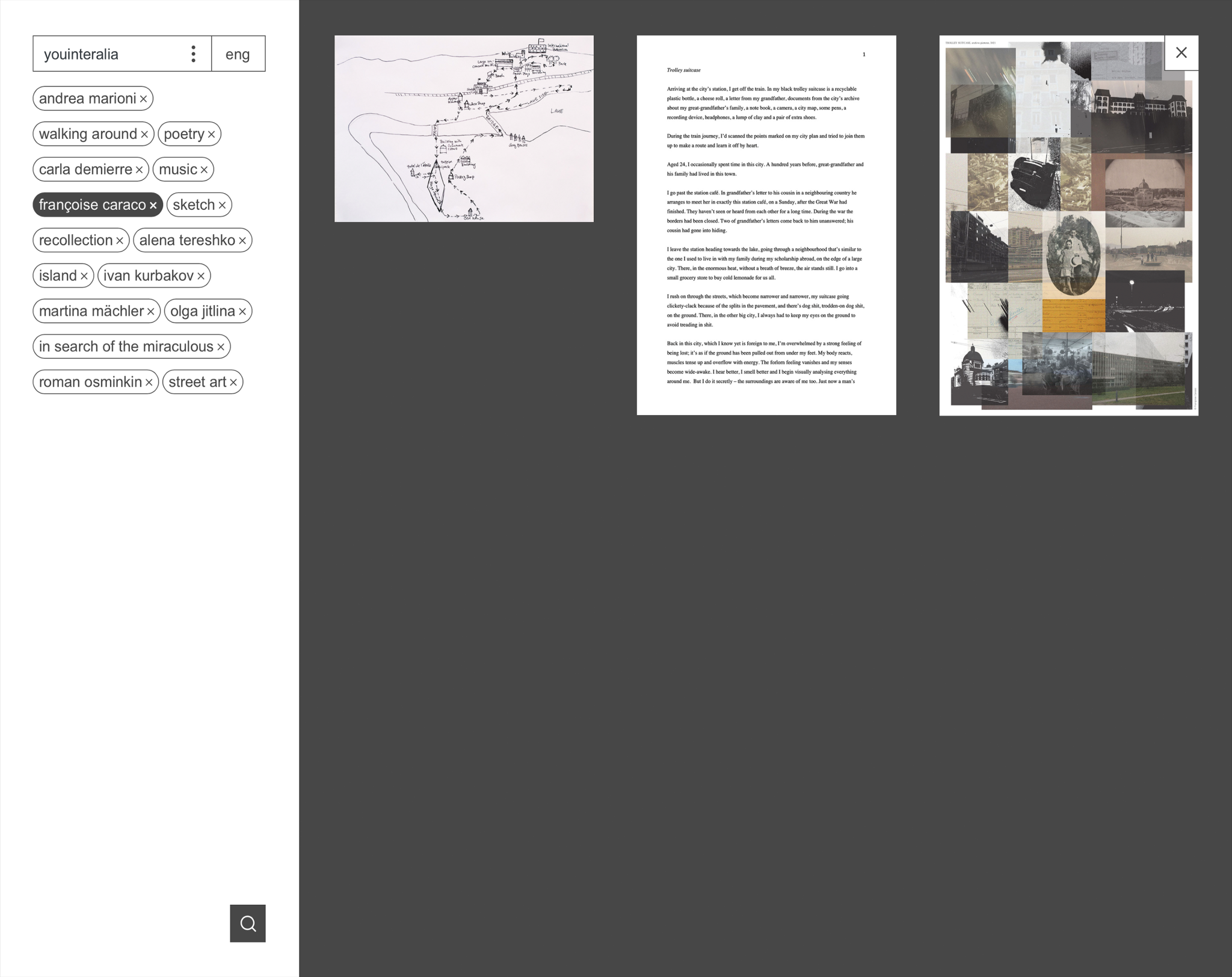

Trolley Suitcase, audio piece about walking and writing, website view from the art-project, you, inter alia, St. Petersburg – Geneva, 2021

Trolley Suitcase, audio piece about walking and writing, website view from the art-project, you, inter alia, St. Petersburg – Geneva, 2021

Trolley Suitcase, audio piece about walking and writing, detail view from the art-project, you, inter alia, St. Petersburg – Geneva, 2021

Trolley Suitcase, audio piece about walking and writing, detail view from the art-project, you, inter alia, St. Petersburg – Geneva, 2021

Audio piece: 32‘ 33‘‘, Spoken by Alma Caraco

Trolley Suitcase, about walking and writing, from the art-project, you, inter alia, St. Petersburg – Geneva, 2021

On the walk through Geneva, I have followed a route to my youthful memories of this city, along lines written down by my grandfather and some contemporary documents about my great-grandfather and his family in connection with their immigration to this city.

The tour starts at the train station and I walk along the lakeshore, through the area of the inner city north of the river, then the part of the city south of the river, and before returning to the train station, I walk up a hill northwest of the train station, and walk from there up to the bottom of the train station.

All the while, walking my chosen route through this city, I drag a trolley suitcase behind me. It stands for travelling itself, but also for carrying memories. The necessary utensils are gathered in the suitcase, for the journey and my artistic exploration.

I am interested in spaces of thought that open up to me while walking or at the chosen places in the city. With a photographic eye, I observe moments of immersion in my own and narrated memories and transfer my thoughts into written language. During my walk through Geneva, I also recorded different city sounds with my recorder.

For the audio piece, I weave these spaces of thought into a narrative voice that is underlaid with recorded city sounds.

Trolley Suitcase is my contribution to the project on «You, inter alia», a web-based intervention by Alina Belishkina and Lera Mostovoya. «You, inter alia» explores space of the city and that of the text through practices of walking and writing, in St Petersburg and Geneva. http://youinteralia.com

Juli 2020

Juli 2020Familienangelegenheit

Ausstellungsansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Detailansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Museum Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Ausstellungsansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Museum Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Ausstellungsansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Museum Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Detailansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Ausstellungsansicht, Familienangelegenheit, Museum Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Audiofile, Familienangelegenheit – Ein Zwiegespräch, Strauhof, Zürich, 2020

Audiostück 23‘ 25“, gesprochen von Esther Becker

15 Farbfoto auf Bütenpapier 420 x 594 mm

Françoise Caraco befasst sich in ihren Arbeiten seit einigen Jahren mit ihrer Familiengeschich-te. Ihre jüngste Recherche hat sie ins Surbtal geführt, nach Endingen, einem ehemaligen «Judendorf». Im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert waren Endingen und das Nachbardorf Lengnau die einzi-gen Orte der Schweiz, in denen sich Juden niederlassen durften. Caracos Urgrossmutter Clara Bollag und weitere Familienmitglieder haben auf dem jüdischen Friedhof Endingens ihre letzte Ruhe gefunden. Aus gesammelten Gesprächssequenzen mit ihrem Vater und dessen Gros-scousine entwirft die Künstlerin ein Zwiegespräch. Caracos Audioarbeit verwebt anhand des Zwiegesprächs Momente des Alltags, der Freude und des Verlusts mit Sequenzen einer Radio-sendung, welche die Herkunft aus dem Surbtal umkreisen. An den Wänden versammelt die Künstlerin skizzenhafte Momentaufnahmen persönlichen Quellenmaterials aus dem Nachlass der Familien Caraco und Wyler und Ausschnitte aus Geschichtsbüchern zu Endingen. Geschichte wird bei Caraco zum fortwährenden, dialogischen Abgleich zwischen individueller und kollektiver Erinnerung.

November 2017

November 2017Grossvaters Dokumente

Ausstellungsansicht, Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung, In the save hands of the artist, Projektraum M54, Basel 2017

Videostill, Grossvaters Dokumente

Video (Ausschnitt), Grossvaters Dokumente

Video, HD 16:9, Zeitdauer 9‘ 54“, Loop, Farbe, Ton

Transkript, 148cm x 34cm

Archive sind private und kollektive Gedächtnisspeicher, die durch das Gezeigte zugleich auf das Fehlende hinweisen. Bei nachforschungen zu lückenhaften Familiengeschichte, sah Caraco im Archiv des Mémorial de la Shoah Dokumente verschollener jüdischer Verwandten ein. Bei der Dokumentation ihrer Recherche lässt sich die Künstlerin im Video – als Teil von Grossvaters Dokumente – in der Tradition der Romantiker in Rückenansicht aufnehmen, wodurch der Zuschauer selber in die Position der Künstlerin / Forscherin gerät. Anstelle einer erhaben Landschaft wird er bei Caraco mit einem Familienschicksal und einem abgründigen kapitel der Geschichte konfrontiert.

Text Ricarda Gerosa / Baharak Omidfard

Juni 2017

Juni 2017Der Kaufmann Caraco

Der Kaufmann Caraco, 2017, Filmpodium Zürich 2017

Der Kaufmann Caraco, 2017, Filmpodium Zürich 2017

Der Kaufmann Caraco, 2017, Filmpodium Zürich 2017

Video (Ausschnitt), Der Kaufmann Caraco, 2017

Der Kaufmann Caraco (2017)

Video, HD 16:9, Zeitdauer 10‘ 48“, Loop, Farbe, s/w, Ton

Der Kaufmann Caraco ist eine knappe, filmische Annäherung der Künstlerin Françoise Caraco an den nahezu vergessenen Spitzenhändler am Rennweg in Zürich. Die Existenz des Mannes, der ihr Urgrossonkel war, zeichnet sie im Video schemenhaft nach, mit der Stimme der gleichnamigen Nebenfigur in Kurt Frühs Film „Hinter den sieben Gleisen“, im Interview mit einer inzwischen verstorbenen Angestellten des Spitzenhändlers, mit dem Wortlaut von Caracos Zürcher Einbürgerungsakte.

September 2015

September 2015Drancy, mémoires à vif (deutsch)

Ausstellungsansicht, Drancy, mémoires, à vif in der Gruppenausstellung Werkschau 2015, Fachstelle Kultur Kanton Zürich, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Foto: Conradin Frei, Zürich

Ausstellungsansicht, Drancy, mémoires, à vif in der Gruppenausstellung Werkschau 2015, Fachstelle Kultur Kanton Zürich, Museum Haus Konstruktiv

Ausschnitt Video, Drancy, mémoires, à vif

Drancy, mémoires à vif, 2015

Video, HD 16:9, Zeitdauer 13' 44", Loop, Farbe, Ton

Seit einigen Jahren befasst sich Françoise Caraco in ihren Arbeiten mit der Familiengeschichte. Als Nachfahrin einer um die Jahrhundertwende nach Basel immigrierten jüdischen Familie ist auch ihre Geschichte vom Holocaust geprägt, der mehrere Vorfahren das Leben gekostet hat. Die Künstlerin interessiert die Verstrickung von persönlicher Geschichte, imaginärer Geschichte und kollektivem Geschichtsbewusstsein. In der gegenwärtigen Arbeit folgt sie wie viele Nachkommen jüdischer Familien den Spuren ihrer Herkunft. Briefe, Fotografien, Erzählungen und Dokumente führten sie in das bei Paris gelegene Sammellager von Drancy, das beinahe alle französischen Juden vor der Deportation durchliefen.

Die einmalige Systematik des Genozids – das unentrinnbare Netz bürokratischer Rationalität der Judenverfolgung – spiegelt sich geradezu im rationalistischen Modernismus des Wohnbaus (Cité de la Muette), der schon vor der Machtübernahme in Frankreich als Gefängnis umgenutzt wurde. Der für Architekturhistoriker bedeutende, damals von der Vichy-Regierung als Sammellager genutzte Baukomplex wird heute bewohnt: Im Bau befinden sich jetzt, wie ursprünglich vorgesehen, Sozialwohnungen. Vor dem Hof des U-förmigen Gebäudekomplexes wurden über die Jahrzehnte hinweg verschiedene Gedenkeinrichtungen installiert, bis zuletzt ein von der französischen Bahn gestifteter Deportationswaggon hingestellt wurde.

Erst 2012 eröffnete auf der Strassenseite gegenüber eine sehr aufwändig eingerichtete, von François Hollande inaugurierte Shoah-Gedenkstätte. Der dafür errichtete Neubau wurde aus den Mitteln nachrichtenloser Vermögen finanziert.

Beim Gang durch den vom Alltag beherrschten Hof hinter dem Deportationswaggon ist viel imaginäre Arbeit verlangt, um sich vorzustellen, was hier einmal geschehen ist. Realitäten, Zeiten kreuzen sich. Der bewohnte Baukomplex ist nicht begehbar. Françoise Caraco meint, im heruntergekommenen Park am Ende des Hofes am ehesten eine Stimmung einfangen zu können. Die Grünanlage wird kaum benutzt, sieht ungepflegt aus, als herrschte hier eine seltsame Berührungsangst, Scham. Die Schablonen vorgefertigter Narrative, auch der von historischen Aufnahmen vorkonfigurierte Blick vermitteln sich stets an der vagen Kenntnis der Geschichte der eigenen Vorfahren und den daraus gemachten Vorstellungen; auch am Jetzt körperlicher Anwesenheit: Diese Vermittlung resultiert, wie die Videoarbeit zeigt, in einem stillen und persönlichen Nachdenken und Umherblicken. Ein «aktives Gedenken», in dem sich greifbar eine Folge des Holocaust für die Nachfahren destilliert: Ein paranoisch flüsterndes – überall da draussen flüsterndes – Selbstgespräch; ein Blick, dem die Welt düster antwortet: ein Unbehagen in der Kultur. Die Künstlerin findet mit ihrer Arbeit eine stabile Form für diesen netzförmigen Schatten auf der Realität. Als «Vierteljüdin» wäre sie, die für die Nachforschungen samt Familie für ein Jahr nach Paris gezogen ist, gemäss Nürnberger Gesetze ebenfalls verfolgt und deportiert worden.

Text: Oliver Caraco

Februar 2015

Februar 2015Grossvaters Dokumente

Ausstellungsansicht Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Detailansicht, Doppelprojektion Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Ausstellungsansicht Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Detailansicht, Transkript, Grossvaters Dokumente, in der Gruppenausstellung Geschichte in Geschichten, Helmhaus Zürich 2015

Audioarbeit: Grossvaters Dokumente, 2015

Grossvaters Dokumente, 2015

Rauminstallation, 2 Videoprojektionen, Audioarbeit und Transkript

Video, HD 16:9, 16'29''/ 20'23'', Audio, 9'54'' gesprochen von Esther Becker

Das Ich in der Geschichte

Das Bild wäre gleich. Würde sich eine Historikerin bei der Arbeit von hinten filmen, sähe das wohl ähnlich aus, wie in der Zweikanal-Videoinstallation von Françoise Caraco: Recherche vor dem Computer, nach Quellen, Informationen, Hinweisen, die dann zu einer historischen Erzählung zusammengefügt werden. Was also unterscheidet eine Künstlerin wie Françoise Caraco von einer Historikerin? Genau dass sie sich eben bei der Arbeit filmt, während eine Historikerin die von ihr erzählte Geschichte für sich sprechen lässt, vielleicht am Ende gar hinter dieser Geschichte verschwinden kann. Heute mag klar sein, dass nicht nur Geschichten geschrieben werden, sondern auch die Geschichte. Von vermeintlich allwissenden Erzählerfiguren, aus einer bestimmten Perspektive, mit ganz bestimmten Interessen. Doch wird das Fach Geschichte bisweilen immer noch gelehrt, als sei ihr Text von einer übermenschlichen Instanz in Stein gemeisselt.

Françoise Caraco steht einer Historikerin in nichts nach. Aus einem Transkript ihrer Begegnung mit einer Mitarbeiterin eines Pariser Archivs, das es sich zum Ziel gemacht hat, Quellenmaterial zu verschollenen jüdischen Personen zu sammeln, wird ersichtlich, mit welcher Genauigkeit Caraco während ihres Aufenthalts in Frankreich nach französischen Verwandten ihres Grossvaters recherchiert hat. Die von ihrem Grossvater hinterlassenen Fotografien und Schriftstücke sind nun auch Teil des Archivs. Und doch ist Caraco keine Historikerin. Denn Caraco erzählt Geschichte in der Ich-Form – in einem auf Kopfhörer zu hörenden Text. Sie geht in dieser Erzählung selbst an der «mur des noms» des Mémorial de la Shoah – das gleich gegenüber ihres temporären Pariser Ateliers liegt und das sie ebenfalls filmisch zeigt – vorbei und liest die dort eingemeisselten Namen Verschwundener. Und sie zeigt sich eben selbst bei der Arbeit. Caraco schreibt das Ich in Geschichte gross.

KünstlerInnen haben von HistorikerInnen viel gelernt. Doch was könnten HistorikerInnen von KünstlerInnen lernen? Zum Beispiel, dass das Medium Video, das in dieser Ausstellung vorherrscht, auch zum Erzählen von Geschichte dienen kann. Und dass man sich hinter einer Kamera genauso gut verstecken kann, wie hinter einer autoritären Autorschaft, die die erste Person ausschliesst. Aber nicht muss, wie Françoise Caraco in Text und Film zeigt.

Text: Daniel Morgenthaler

November 2013

November 2013Ablagerung

Ortsspezifische Installation, Audioarbeit; Begegnungen, die keine sind, im Spitzengeschäft Caraco Basel, 2013

Aussenansicht des Spitzengeschäfts Caraco Basel, 2013

Ortsspezifische Installation, Reisebericht: Fremde Erinnerungen, im Spitzengeschäft Caraco Basel, 2013

Ortsspezifische Installation, Ablagerung, im Spitzengeschäft Caraco Basel, 2013

Ortsspezifische Installation, Hinterräume, 8 Videos in der Ausstellung Ablagerung, im Spitzengeschäft Caraco Basel, 2013

Audiostück; Begegnungen, die keine sind, 2013

Ablagerung (2013)

Ortspezifische Installation im Spitzengeschäft Caraco 2013:

Audioarbeit: Begegnungen, die keine sind, 13' 12'' im Loop

Reisebericht: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint

Videos auf acht Monitoren, Hinterräume, HD 16:9, unterschiedliche Abspieldauer im Loop

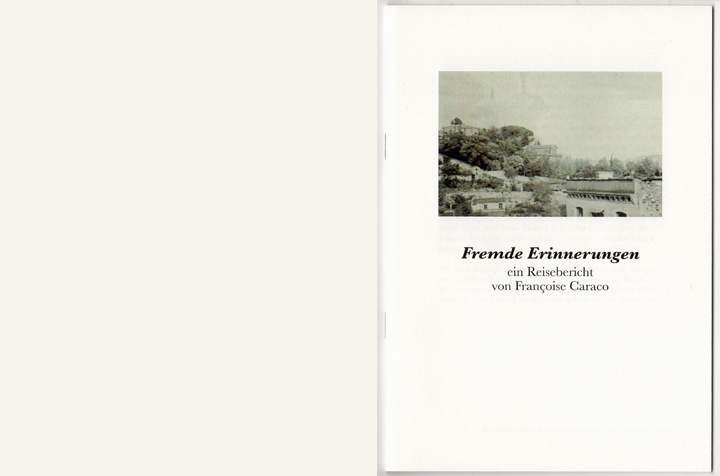

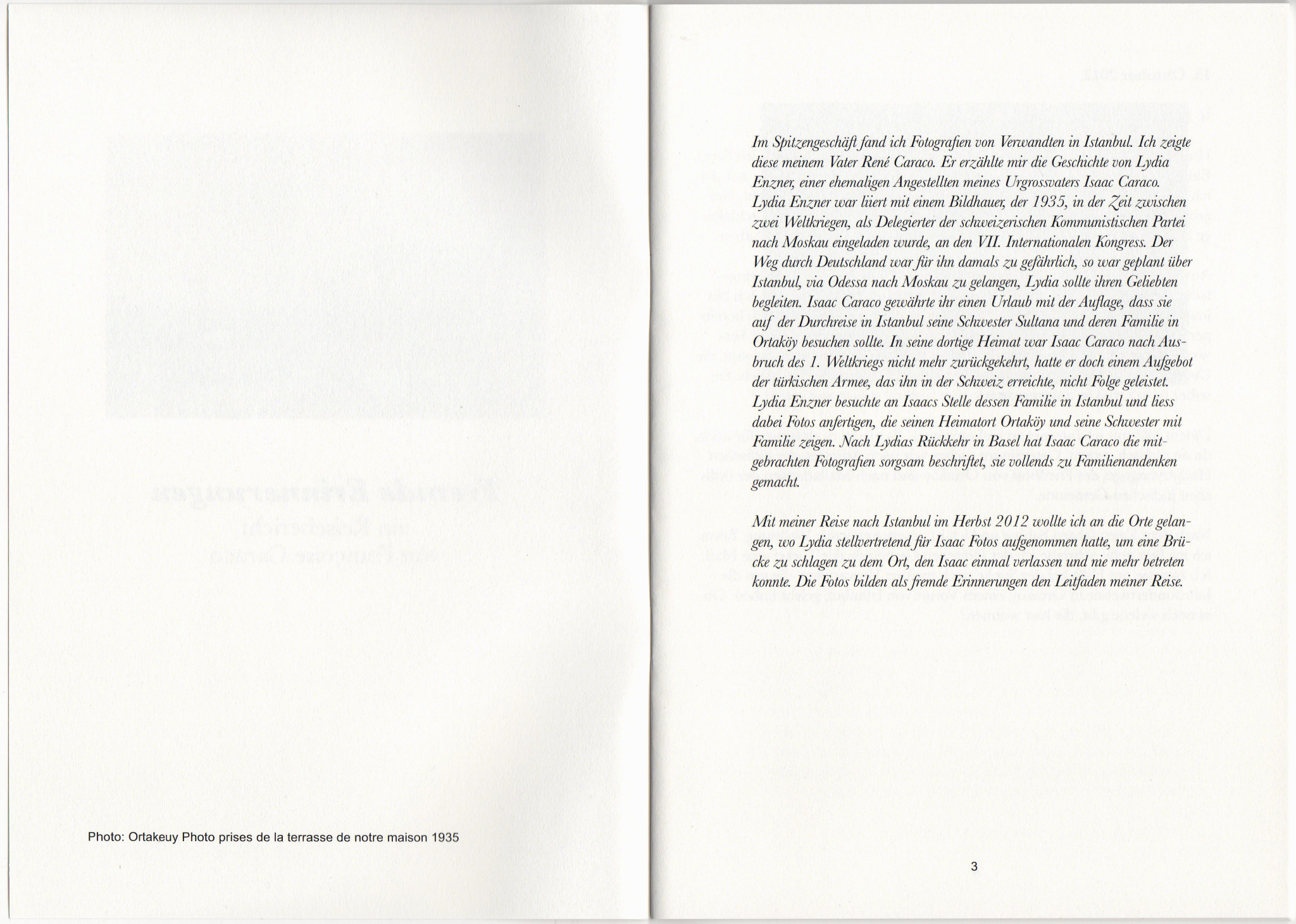

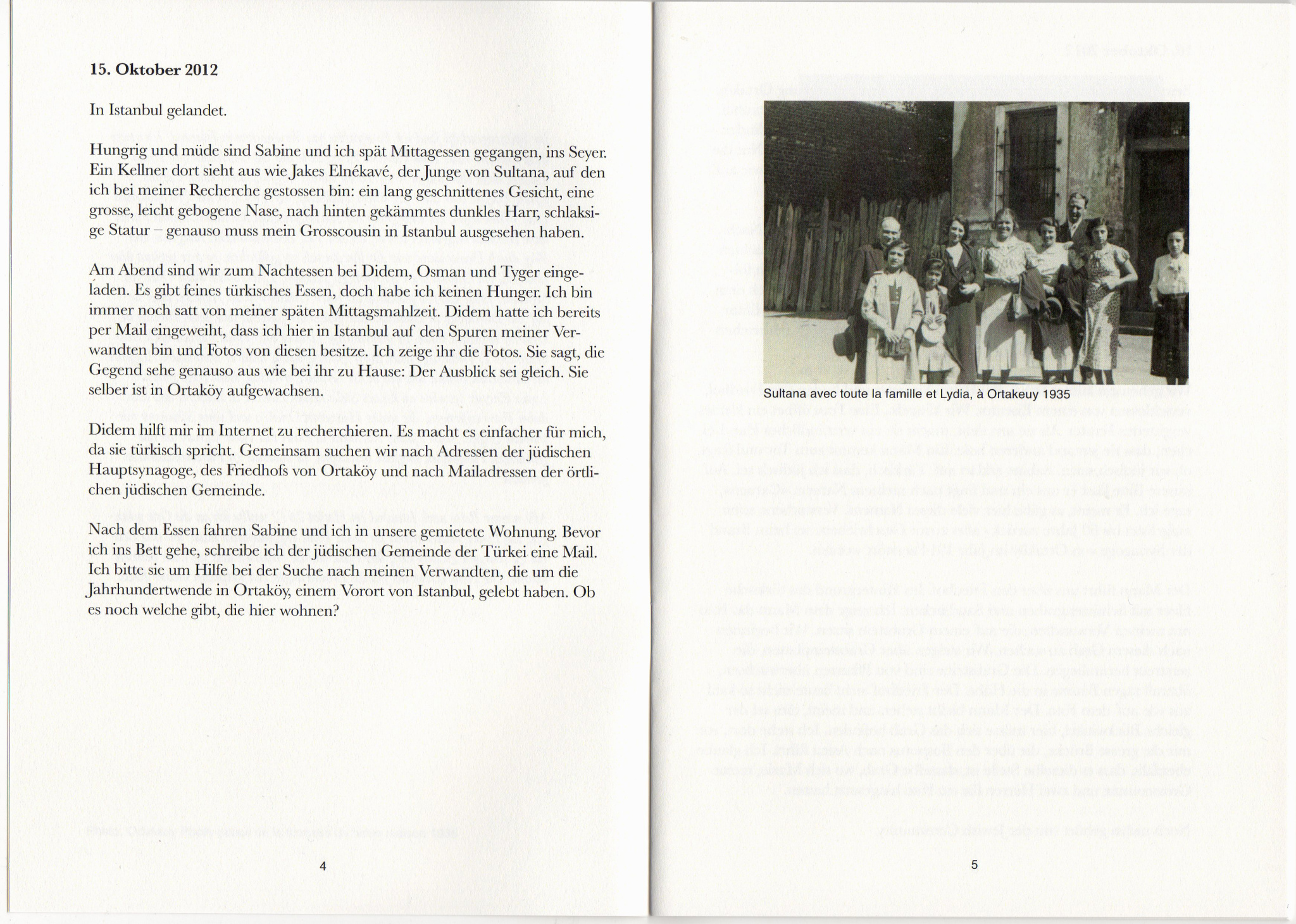

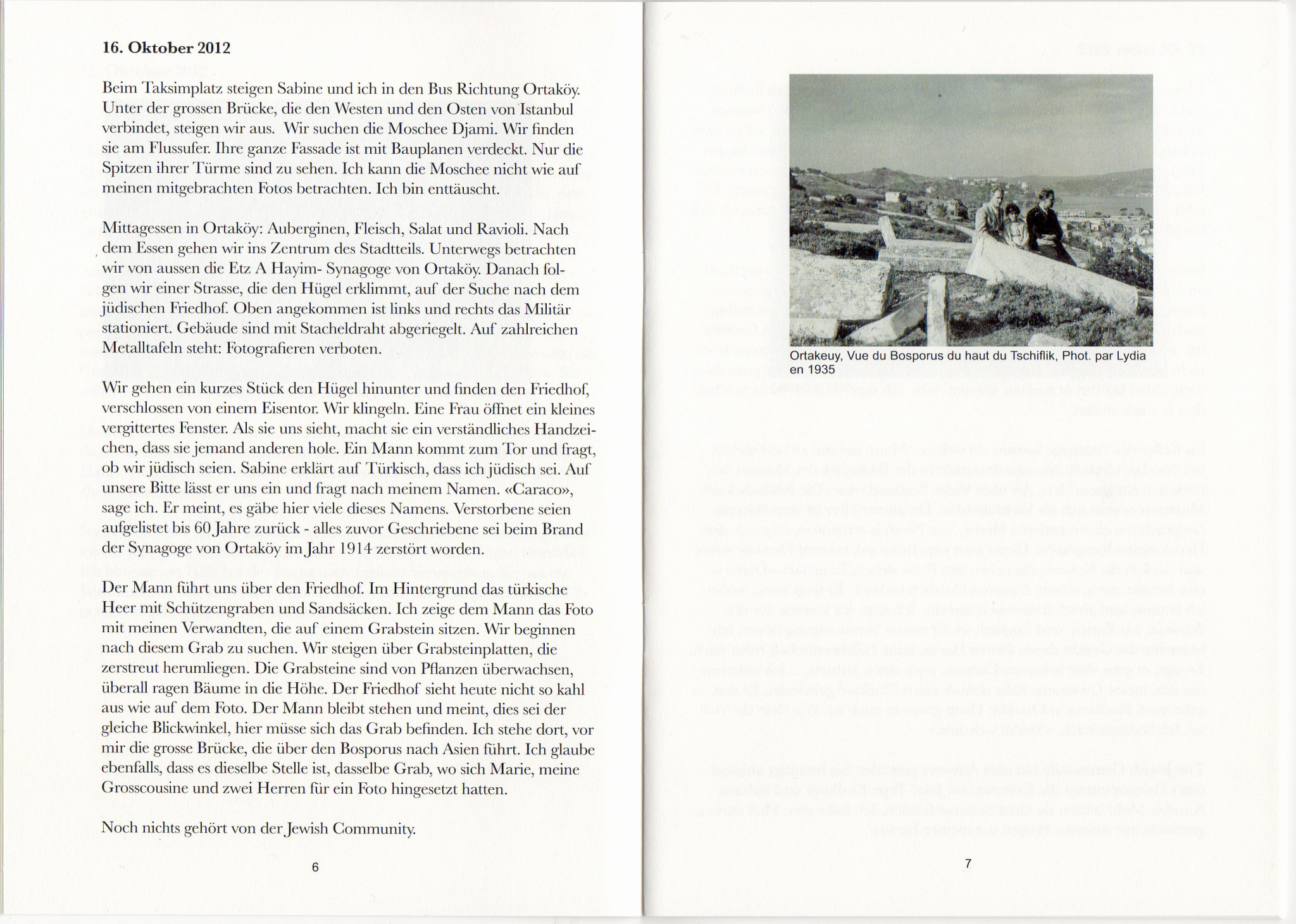

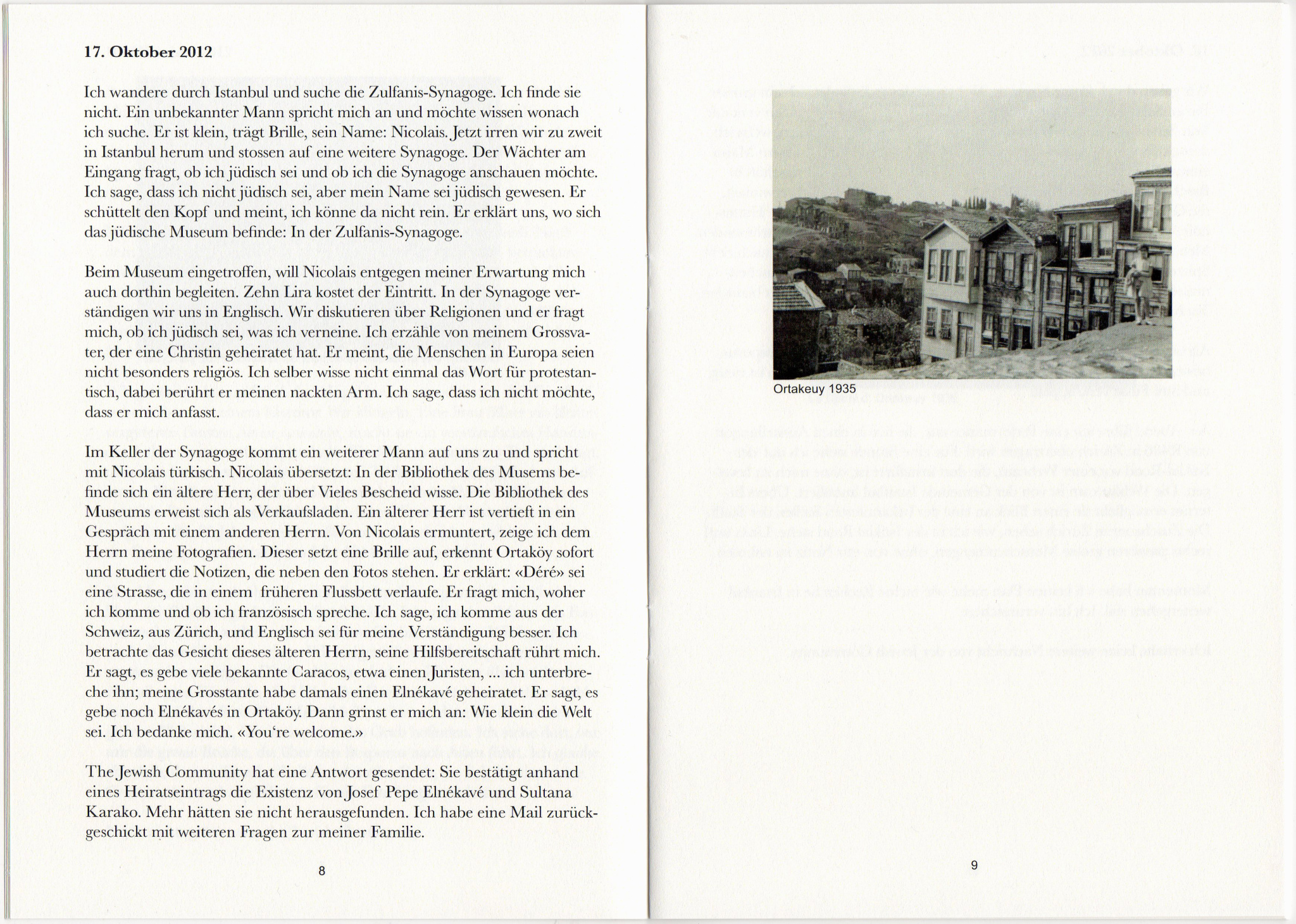

Das Spitzenwarengeschäft «Caraco» ist Ausgangs- und Endpunkt für Françoise Caracos ortsspezifische Installation «Ablagerung». Im Jahr 1914 von ihrem Urgrossvater Isaac Caraco, einem jüdischen Kaufmann aus dem damaligen Konstantinopel, in Basel eröffnet, ging es später an ihren Grossvater Robert über. Noch heute gehört die Liegenschaft an der Gerbergasse 77 der Familie Caraco. Die Arbeit «Ablagerung» ist ein künstlerischer Eingriff, der bei der Suche nach der eigenen Geschichte an einem Schauplatz der Familiengeschichte ansetzt. Sie besteht aus Audiofragmenten («Begegnungen, die keine sind»), einem Reisebericht («Fremde Erinnerungen») und Videos («Hinterräume») im Schaufenster auf Seite der Falknerstrasse.

Geschichte spielt im Raum und in der Zeit. Das Spitzenwarengeschäft «Caraco» legt davon ein beredtes Zeugnis ab. Während das Gerüst der Zeit fast wie von selbst Erzählungen erzeugt und Ordnung schafft, gebietet der Ort in dieser Hinsicht Widerstand. Alles, was war und ist, erscheint hier auf einen Schlag. Was ist, ist nach allen Seiten offen, es herrscht die Gleichzeitigkeit der Ungleichzeitigkeit. Darauf verweisen die acht Videos der Arbeit «Hinterräume».

Einige Kartonschachteln Archivmaterial hat die Künstlerin geöffnet, sie haben Briefe und Fotografien, Kassenbelege und wertvolle Spitzen zutage gebracht. Viele Schachteln aber bleiben gestapelt und ungeöffnet. Es sind Ablagerungen, die als Zeichen vergangener Zeiten ins Heute hineinreichen. Dass ihre Oberflächen staubig bleiben, nimmt ihnen nicht ihre Bedeutsamkeit. Wie man sich selbst nie abschliessend und nur erzählend erfassen kann, so weist jede Ahnenforschung und Geschichts-schreibung Lücken auf. Wo etwas in Erfahrung gebracht wird, geht anderswo ein neues unbekanntes Feld auf.

Die ungeöffneten Archivschachteln stehen stellvertretend für dieses Nichtwissen. Kein Leben und kein geschichtlicher Zusammenhang lässt sich mimetisch erzählen – nur schon, weil dann die Erzählung genau so lange dauern müsste wie das Leben selbst oder eine Ereignisfolge an sich. Erst die Auslas-sungen und Hervorhebungen zeigen etwas vom Selbst oder vom Früher. Françoise Caracos Installation legt die Vermutung nahe, dass die erzählerische Konfiguration in diesem Zusammenhang als Bedingung für Wahrhaftigkeit gelten kann.

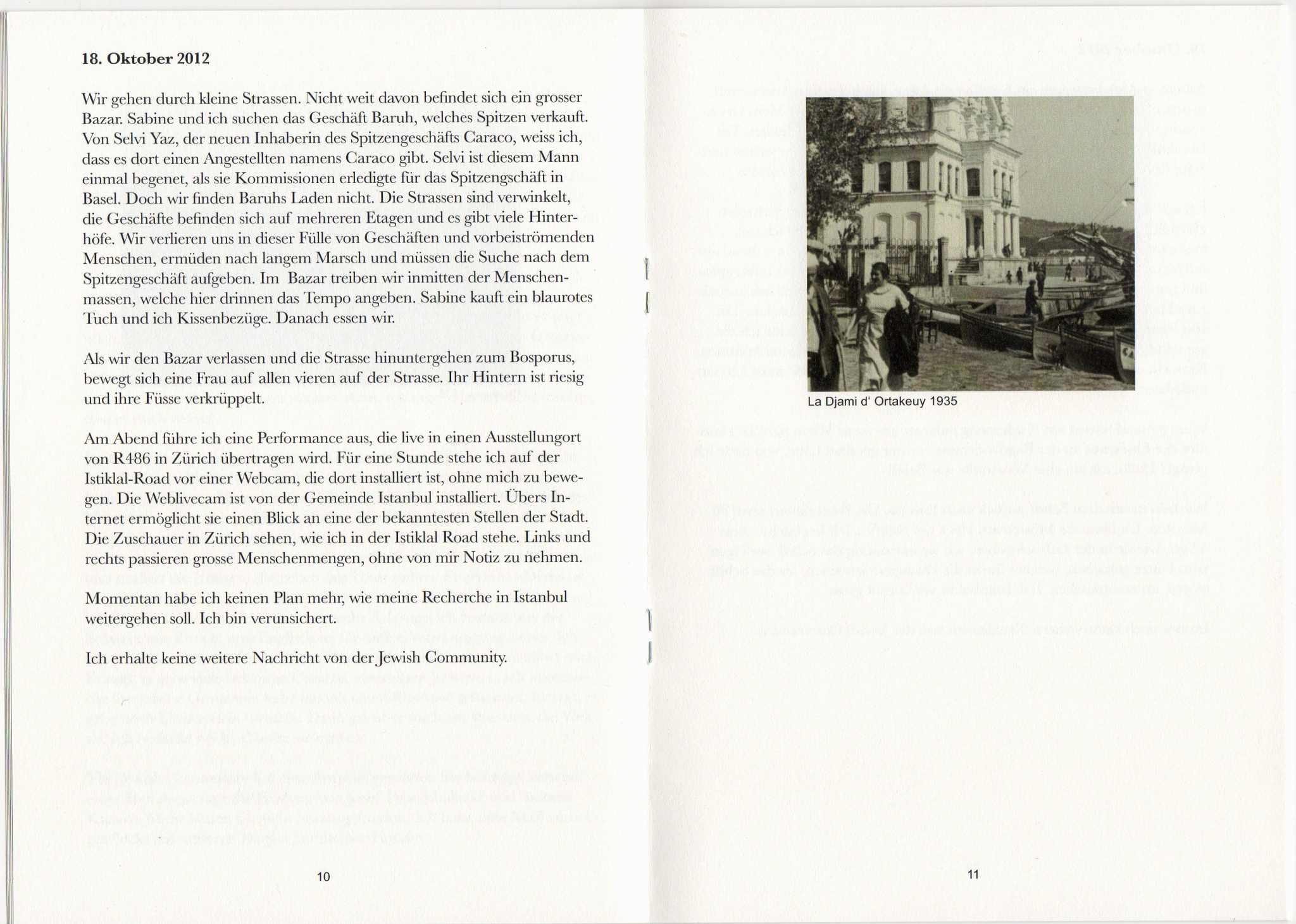

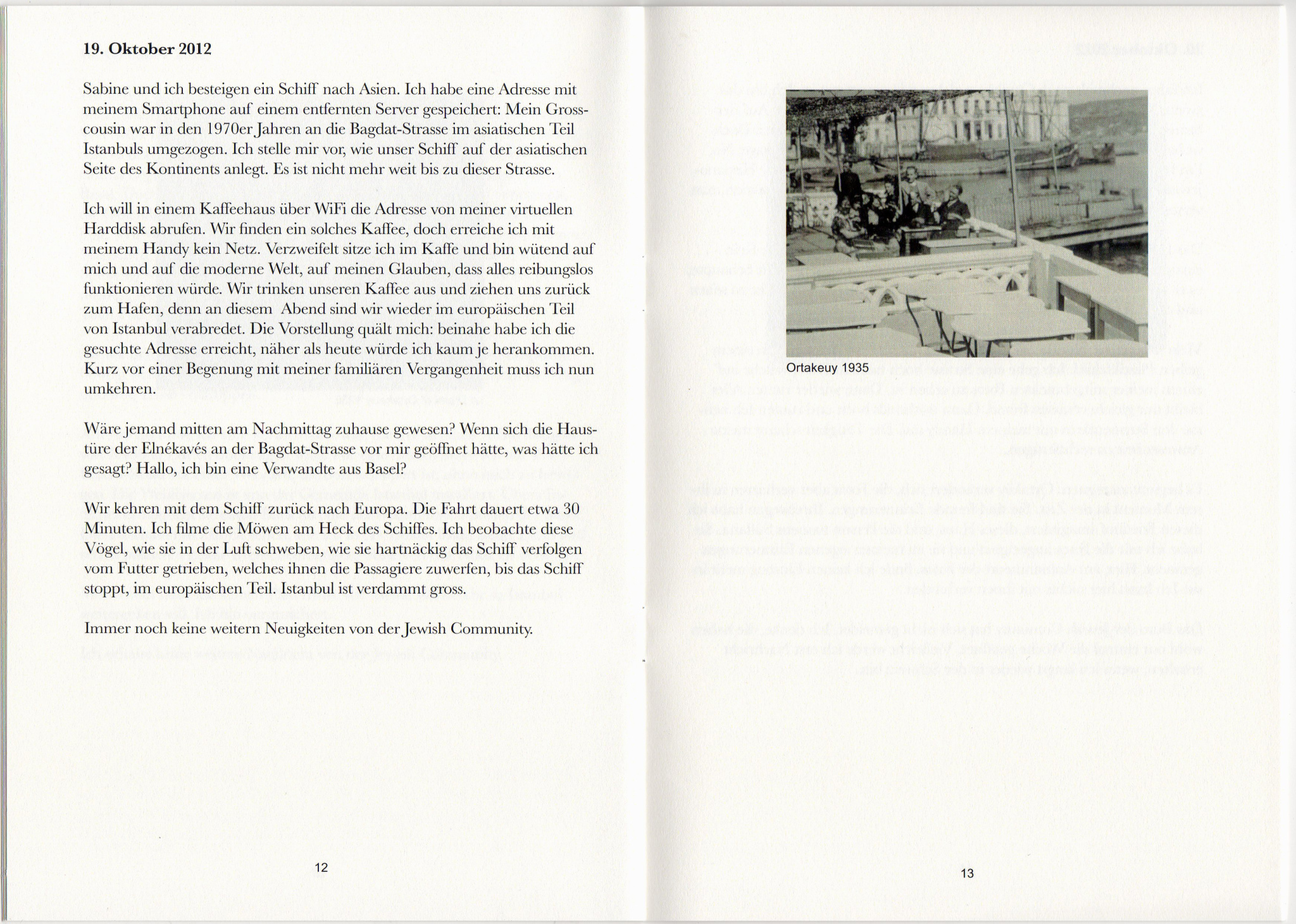

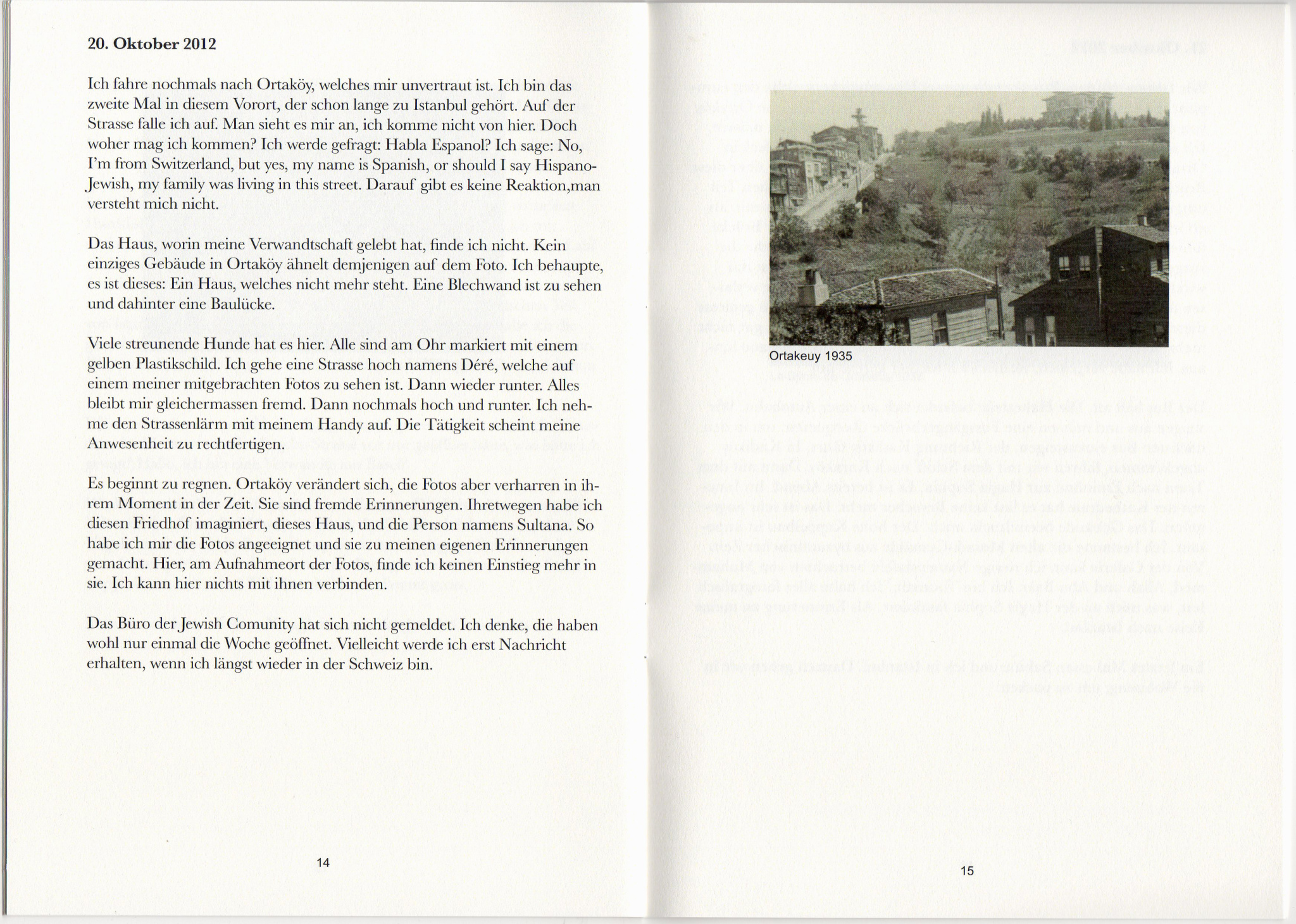

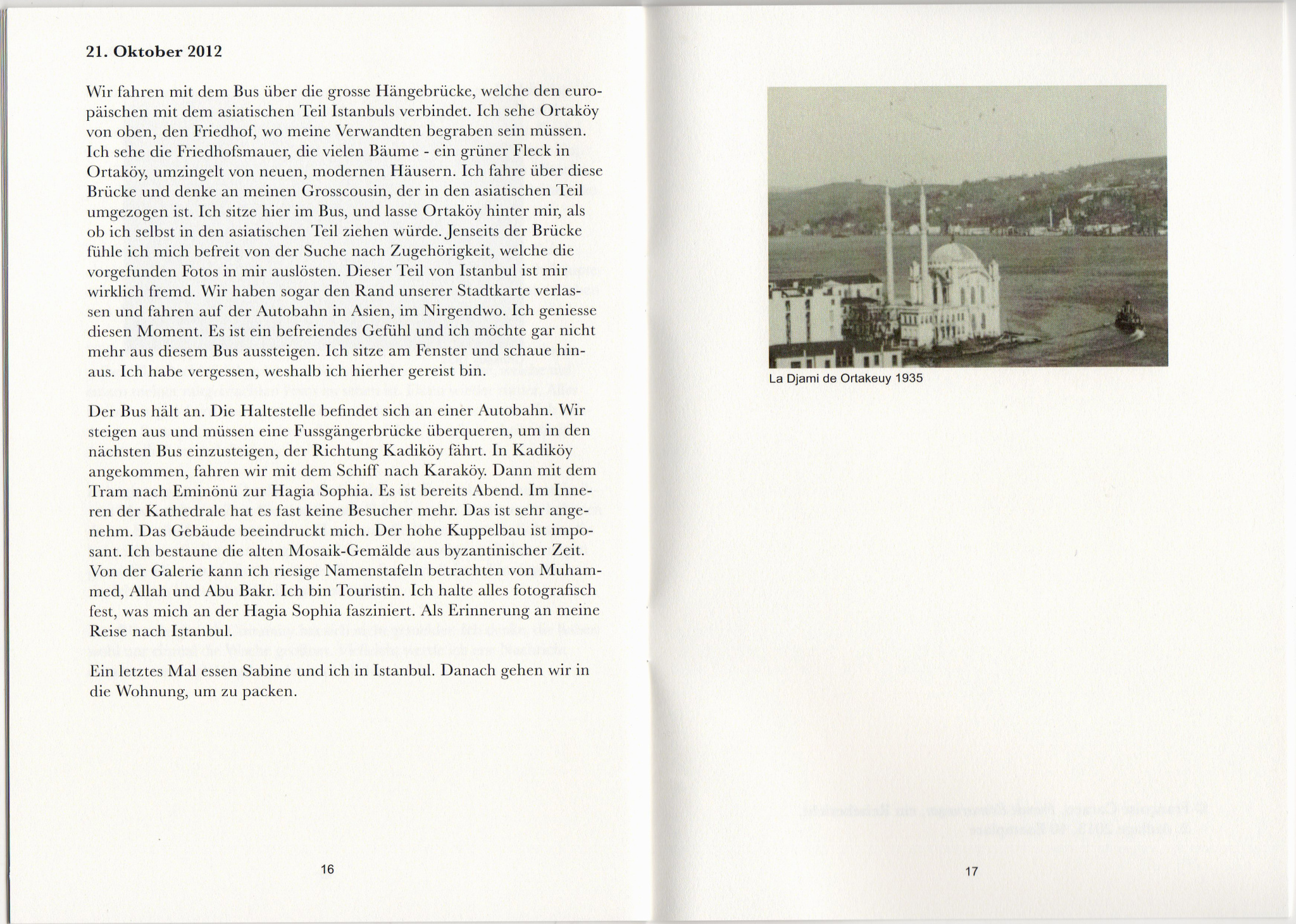

Jede Suche nach der eigenen Geschichte hat mit Versäumnissen und Unausgesprochenem umzugehen. Von dieser Erfahrung sprechen der Reisebericht «Fremde Erinnerungen» und die Audiofragmente «Begegnungen, die keine sind». Für den Reisebericht ist die Künstlerin mit Familienfotos aus dem Jahr 1935, die den Geburtsort Ortaköy ihres Urgrossvaters zeigen, in die Türkei gereist. Das Vorhaben, den Fotografien entsprungene Vorstellungen mit der Erfahrung vor Ort anzugleichen, verliert in Ortaköy seine Selbstverständlichkeit. Die Konfrontation macht aus der Suchenden eine Besucherin, die nach-drücklich bemerken muss, dass es Fremdes in ihrer Geschichte gibt, das fremd bleiben wird.

Ähnlich verhält es sich mit dem Versuch, ein Gespräch mit der Verwandtschaft aufzunehmen. In «Begegnungen, die keine sind» verweben sich Korrespondenzfetzen, die ihr Urgrossvater und Gross-vater hinterlassen haben, mit dem zaghaften Austausch unter den lebenden Familienmitgliedern.

Der fragmentarische Charakter der Audioaufzeichnung verweist auf Lücken, ohne die eine Erzählung nicht auskommen kann. Die eigentliche Kraft der Erzählung, Erfahrungen der Dissonanz zu glätten, Übergänge und Unverstandenes zu plausibilisieren, wird in Françoise Caracos Installation jedoch nicht eingesetzt. Damit steht ihre Suche nach der eigenen Geschichte auch für ein generelles Un-vermögen, das jeden Blick zurück und auf sich selbst mitbestimmt.

In Françoise Caracos Arbeit «Ablagerung» ist es nicht eine kohärente Erzählung, die den Zusammen-hang aufrecht erhält, sondern die Räumlichkeiten des Spitzenwarengeschäfts «Caraco» an sich – als Drehscheibe der Geschichte.

Text: Alain Gloor

November 2013

November 2013Reisebericht, Fremde Erinnerungen, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Reisebericht A5: Fremde Erinnerungen, Laserprint, 2013

Juli 2013

Juli 2013Familienfotos I, II, III

Ausstellungsansicht: Familienfotos I,II, III, in der Gruppenausstellung Stipendien- und Atelierwettbewerb, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detailansicht: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detailansicht: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detailansicht: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Detailansicht: Familienfotos I,II, III, Helmhaus Zürich 2013

Audiostück: Familienfotos III, 5' 32'', im loop

Ausschnitt Video: Familienfotos I, HD 16:9, 2:33 min

Familienfotos I, II, III, (2013)

I: Videoprojektion, HD 16:9, Zeitdauer 2' 33", loop

II: 26, A5 Karteikarten, Laser-print auf Papier

III: Audiostück, Zeit 5' 30", loop, gesprochen von Esther Becker

Françoise Caraco setzt sich mit der Lebensgeschichte ihrers Grossvaters auseinander. Die Vertiefung in die persönliche Familiengeschichte stellt dabei für die Künstlerin eine Geste der Aufschliessung dar: Sie dient ihr als Anlass, die Umstände des Öffentlichen und Politischen einer vergangenen Zeit zu rekonstruieren und reflektieren. Françoise Caraco erstellt in der Arbeit Familienfotos eine Versuchsanordnung, und thematisiert die Grenzziehungen der familiären und gesellschaftlichen Zugehörigkeit. Sie verwendet dazu Portraitbilder und Informationsbruchstücke aus Briefen von 1904 bis 1941, die ihr Grossvater, Sohn eines sefardisch-jüdischen Einwanderers aus Istanbul, aufbewahrt hatte.

Familienfotos ist eine räumliche Installation, in der Françoise Caraco eine Sammlung von Fotografien und Textfragmenten aus dem Nachlass ihres Grossvaters inszeniert. Aus ihrer heutigen Perspektive wiederholt Caraco den Versuch ihres Grossvaters, sich anhand von Familienfotos und Schriftstücken der Gegenwärtigkeit seiner Verwandten zu vergewissern. Als Ausgangsmaterial für Caraco dienen Fotografien, Postkarten und Briefkorrespondenz, die sich die weltweit verstreuten Verwandten von ihrer jeweils neuen «Heimat» zugesandt hatten. In Caracos Inszenierung werden sie zu Zeitdokumenten, die wenig über die konkreten Lebensumstände der Familie verraten und mehr Fragen über die Lage des Öffentlichen aus intimer Perspektive aufwerfen.

Die Künstlerin hat das vorhandene und lückenhafte Archivmaterial vom Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts sorgfältig überprüft, inhaltlich interpretiert und formal verwandelt. Übliche schwarz-weisse Familieportraits aus dieser Zeit, hat sie in kurze Texte übersetzt. In diesen Texten versucht sie beschreibend die Beziehungen zwischen den abgebildeten Personen untereinander und mit dem ebenfalls abgebildeten Kontext zu rekonstruieren. Schriftliche Angaben zu Daten und Ortschaften, aus denen die jeweiligen Bilder stammen, hat Caraco von einer Schauspielerin in Form einer trockenen Auflistung laut vorlesen lassen. Die leeren Rückseiten der Fotos, auf denen die Mitglieder der Verwandtschaft abgebildet sind, hat sie zu abstrakten Bildern gemacht, die sie - in Abwechslung mit Textfragmenten aus der Briefkorrespondenz – auf einer Wand projiziert. Durch diese drei verschiedenen Formen der Übersetzung rekonstruiert Caraco Beziehungen und Zusammenhänge, die ein neues gegenwärtiges Bild einer Vergangenheit erschaffen. Die leeren Rückseiten und die fragmentierten Texte weisen aber auch auf Verlust und Lücke hin.

In der Arbeit Familienfotos befragt Caraco im weitesten Sinne das Medium Fotografie, als dokumentarische Form. Was kann Fotografie überliefern und wie? Welche sind ihre Wahrheitsansprüche und Möglichkeiten? Caraco versteht die Fotografie als Dokument, welches nicht immer leicht lesbar ist. So waren für sie die Fotografien aus dem Nachlass ihres Grossvaters anfangs nicht entschlüsselbar. Die darauf abgebildeten Personen konnte sie weder erkennen noch einordnen. Ausgehend aus gleichem Quellmaterial, in dem Versuch dieses lesbar zu machen, hat Caraco drei verschiedene Formen der Übersetzung erarbeitet, welche die flüchtigen Dokumente mit neuer Konsistenz versehen. Ob sich aus diesen Übersetzungen eine persönliche Vergangenheit zusammensetzen lässt bleibt offen: Handelt es sich nicht doch lediglich um eine konstruierte Wirklichkeit, eine Fiktion? An diesem Punkt stossen wir wieder auf ein von Hito Steyerl ans Licht gebrachtes Paradox: «Der Zweifel an ihren Wahrheitsansprüchen macht dokumentarische Bilder nicht schwächer sondern stärker».

Text: Irene Grillo, 2013

Februar 2013

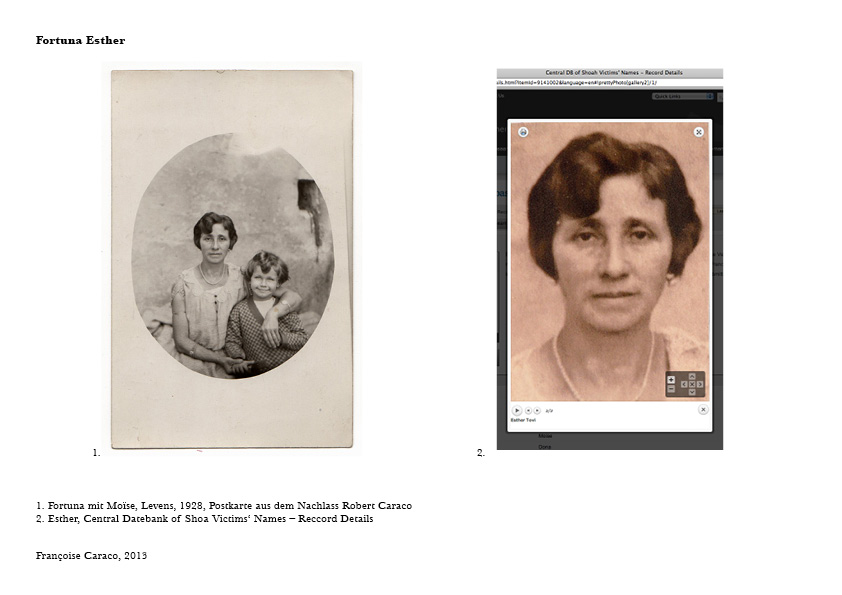

Februar 2013Fortuna Esther

Lecture Performance von Françoise Caraco, anlässlich der Ausstellung, Fergangenheit Fake Fiktion, in Zusammenarbeit mit Nicole Biermaier, Corner College, Zürich 2013

Beiblatt zur Lectureperformance von Françoise Caraco, Fortuna Esther

Fortuna Esther (2013)

Lecture Performance von Françoise Caraco + Nicole Biermaier, anlässlich der Ausstellung Fergangenheit, Fake, Fiktion, Corner College Zürich

In meiner Lecture Performance erzähle ich, wie ich am Beispiel eines persönlichen Familienfotos erfahren muss, wie schwierig es sein kann, im Nachhinein die Existenz verstorbener Personen zu rekonstruieren, wenn deren Geschichte lückenhaft ist.

Ich bin auf zwei Fotos einer mir Verwandten Frau gestossen, mit jeweils unterschiedlicher Identifizierung -einmal als Fortuna, einmal als Esther. Es entsteht Zweifel daran, dass die Fotografie, als Beweismittel als Identitätsstiftende Kraft dienen kann.

Dass es Fortuna und Esther gegeben hat, daran besteht kein Zweifel, beide sind erwähnt in Grossvaters Ahnenschrift, ebenfalls sind beide Frauen aufgelistet in einer Shoah-Datenbank. Doch welche von beiden Frauen mir jetzt auf dem Foto gegenübersitzt und den jungen Moïse in den Armen hält, bleibt unklar.